Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. [Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74(https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa426)).

See the 2020 paper titled "DSSR-enabled innovative schematics of 3D nucleic acid structures with PyMOL" in Nucleic Acids Research and the corresponding Supplemental PDF for details. Many thanks to Drs. Wilma Olson and Cathy Lawson for their help in the preparation of the illustrations.

Details on how to reproduce the cover images are available on the 3DNA Forum.

Structure of a group II intron ribonucleoprotein in the pre-ligation state (PDB id: 8T2R; Xu L, Liu T, Chung K, Pyle AM. 2023. Structural insights into intron catalysis and dynamics during splicing. Nature 624: 682–688). The pre-ligation complex of the Agathobacter rectalis group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase with intron and 5′-exon RNAs makes it possible to construct a picture of the splicing active site. The intron is depicted by a green ribbon, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs represented as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; the 5′-exon is shown by white spheres and the protein by a gold ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Complex of terminal uridylyltransferase 7 (TUT7) with pre-miRNA and Lin28A (PDB id: 8OPT; Yi G, Ye M, Carrique L, El-Sagheer A, Brown T, Norbury CJ, Zhang P, Gilbert RJ. 2024. Structural basis for activity switching in polymerases determining the fate of let-7 pre-miRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 31: 1426–1438). The RNA-binding pluripotency factor LIN28A invades and melts the RNA and affects the mechanism of action of the TUT7 enzyme. The RNA backbone is depicted by a red ribbon, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs represented as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; TUT7 is represented by a gold ribbon and LIN28A by a white ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Cryo-EM structure of the pre-B complex (PDB id: 8QP8; Zhang Z, Kumar V, Dybkov O, Will CL, Zhong J, Ludwig SE, Urlaub H, Kastner B, Stark H, Lührmann R. 2024. Structural insights into the cross-exon to cross-intron spliceosome switch. Nature 630: 1012–1019). The pre-B complex is thought to be critical in the regulation of splicing reactions. Its structure suggests how the cross-exon and cross-intron spliceosome assembly pathways converge. The U4, U5, and U6 snRNA backbones are depicted respectively by blue, green, and red ribbons, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs shown as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; the proteins are represented by gold ribbons. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Structure of the Hendra henipavirus (HeV) nucleoprotein (N) protein-RNA double-ring assembly (PDB id: 8C4H; Passchier TC, White JB, Maskell DP, Byrne MJ, Ranson NA, Edwards TA, Barr JN. 2024. The cryoEM structure of the Hendra henipavirus nucleoprotein reveals insights into paramyxoviral nucleocapsid architectures. Sci Rep 14: 14099). The HeV N protein adopts a bi-lobed fold, where the N- and C-terminal globular domains are bisected by an RNA binding cleft. Neighboring N proteins assemble laterally and completely encapsidate the viral genomic and antigenomic RNAs. The two RNAs are depicted by green and red ribbons. The U bases of the poly(U) model are shown as cyan blocks. Proteins are represented as semitransparent gold ribbons. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Structure of the helicase and C-terminal domains of Dicer-related helicase-1 (DRH-1) bound to dsRNA (PDB id: 8T5S; Consalvo CD, Aderounmu AM, Donelick HM, Aruscavage PJ, Eckert DM, Shen PS, Bass BL. 2024. Caenorhabditis elegans Dicer acts with the RIG-I-like helicase DRH-1 and RDE-4 to cleave dsRNA. eLife 13: RP93979. Cryo-EM structures of Dicer-1 in complex with DRH-1, RNAi deficient-4 (RDE-4), and dsRNA provide mechanistic insights into how these three proteins cooperate in antiviral defense. The dsRNA backbone is depicted by green and red ribbons. The U-A pairs of the poly(A)·poly(U) model are shown as long rectangular cyan blocks, with minor-groove edges colored white. The ADP ligand is represented by a red block and the protein by a gold ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Moreover, the following 30 [12(2021) + 12(2022) + 6(2023)] cover images of the RNA Journal were generated by the NAKB (nakb.org).

Cover image provided by the Nucleic Acid Database (NDB)/Nucleic Acid Knowledgebase (NAKB; nakb.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

I recently came across a Bioinformatics article VeriNA3d: an R package for nucleic acids data mining by Gallego et al. from IRB Barcelona. VeriNA3d can perform dataset analysis, single-structure analysis, and exploratory data analyses, with an emphasis on complex RNA structures. I am glad to see the DSSR is one of the third-party utilities that have been integrated into VeriNA3d, as shown below

VeriNA3d offers integration with third-party utilities such as the non-redundant lists of RNA structures (Leontis and Zirbel, 2012), the eRMSD suggested to compare RNA structures (Bottaro et al., 2014), a wrapper to the DSSR (Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA) software (Lu et al., 2015) and query functions to access the PDBe REST API (Velankar et al., 2016).

I browsed the GitLab repository and read through the supplemental documents. Clearly, VeriNA3d is a handy tool for the R community to perform RNA 3D structural analyses.

To DSSR users, Section “9 The dssr wrapper: getting the base pairs” of the supplemental PDF “VeriNA3d: introduction and use cases” is particularly relevant. The three paragraphs (with minor edits) are excerpted below:

The DSSR software (Dissecting the Spatial Structure of RNA) (Lu, Bussemaker, and Olson 2015) represents an invaluable resource to handle RNA structures. Some of the functions of veriNA3d overlap with the functionalities of DSSR, and both applications provide unique different features. We implement a wrapper to execute DSSR directly from R and get the best of both worlds in one place.

Note that installing veriNA3d does not automatically install DSSR, since we don’t redistribute third-party software. Before any user can use our wrapper, the dssr function, DSSR should be installed separately. To address this installation we redirect you to the DSSR manual, where anyone can find the specific instructions for their system. Once DSSR is installed and working in your computer, you will also be able to use it with our wrapper. If the DSSR executable (named x3dna-dssr) is in your path, dssr will find it automatically. If the wrapper does not find it, you can still use it specifying the absolute path to the executable with the argument exefile. Find more information running ?dssr.

One of the DSSR capabilities that users might be interested in is the detection and classification of base pairs. The following code shows a simple example. The output of the dssr wrapper is an object got from the json DSSR output. From R, json objects are parsed in the form of a tree of lists, with different types of information. Most of the interesting data is under the list models, sublist parameters, as shown herein.

I echo the authors’ policy of not redistributing third-party software with VeriNA3d. DSSR is under active development. Users should always visit the 3DNA Forum for downloading the latest version of DSSR, reporting bugs, and asking questions.

The R interface to DSSR (via JSON output) in VeriNA3d represents one of the intended use cases of DSSR’s many possible applications. No doubt DSSR is being increasingly integrated into other resources of RNA structural bioinformatics. Hopefully, more advanced DSSR features (than the detection and classification of base pairs) will also be widely appreciated in the future. Users would love DSSR better when they gain more experience in structural bioinformatics.

It is a great pleasure to see that our article Web 3DNA 2.0 for the analysis, visualization, and modeling of 3D nucleic acid structures has been highlighted in the cover page of the web server issue of NAR’19. According to the editor, This year, 331 proposals were submitted and 122, or 37%, were approved for manuscript submission. Of those approved, 94, or 77%, were ultimately accepted for publication. Overall, that corresponds to a ~28% acceptance rate.

The cover image and its caption are shown below. Moreover, details on how the cover image was created are available on the 3DNA Forum.

Caption: Examples of customized molecular models that can be generated with 3DNA: (top) a chromatin-like, nucleosome-decorated DNA with the structures of known histone-DNA assemblies placed at user-defined binding sites; (lower left) molecular schematic of a DNA trinucleotide diphosphate illustrating the base planes and reference frames used to construct and analyze 3D nucleic acid-containing structures; (lower right) customized single-stranded tRNA model built from a user-defined base sequence and a set of rigid-body parameters describing the desired placement of successive bases. Color code of base blocks: A, red; C, yellow; G, green; T, blue; U, cyan.

While browsing the June 2019 issue of the RNA journal, I was surprised to see a cover image with familiar schematic representations:

The caption is as below:

Crystal structure of ykoY-mntP riboswitch chimera bound to cadmium (Protein Data Bank code: 6cc3; Bachas ST, Ferré-D’Amaré AR. 2018. Convergent use of heptacoordination for cation selectivity by RNA and protein metalloregulators. Cell Chem Biol 25: 962–973.e5). The RNA backbone is displayed as a red ribbon; bases are shown as blocks with NDB coloring: A—red, C—yellow, G—green, U—cyan; cadmium ions are shown as red spheres. The image was generated using 3DNA/blocview and PyMol software. Cover image provided by the Nucleic Acid Database (ndbserver.rutgers.edu).

In addition to the blocview script distributed with 3DNA v2.x, the block-view has been integrated into DSSR via the --blocview option. Notably, the DSSR-plugin introduces the dssr_block command to PyMOL for interactive visualization of nucleic acid structures. See the DSSR User Manual for more information.

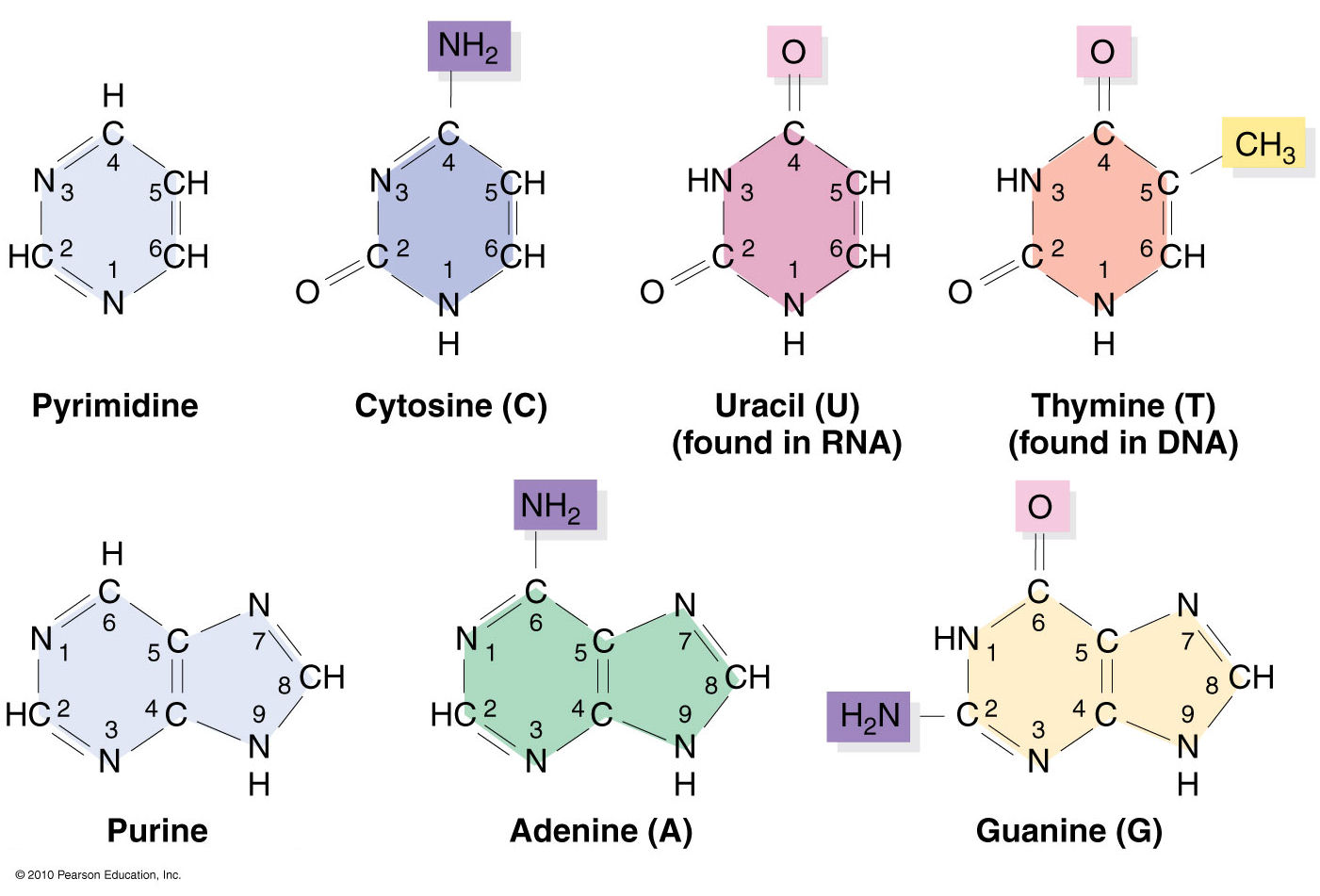

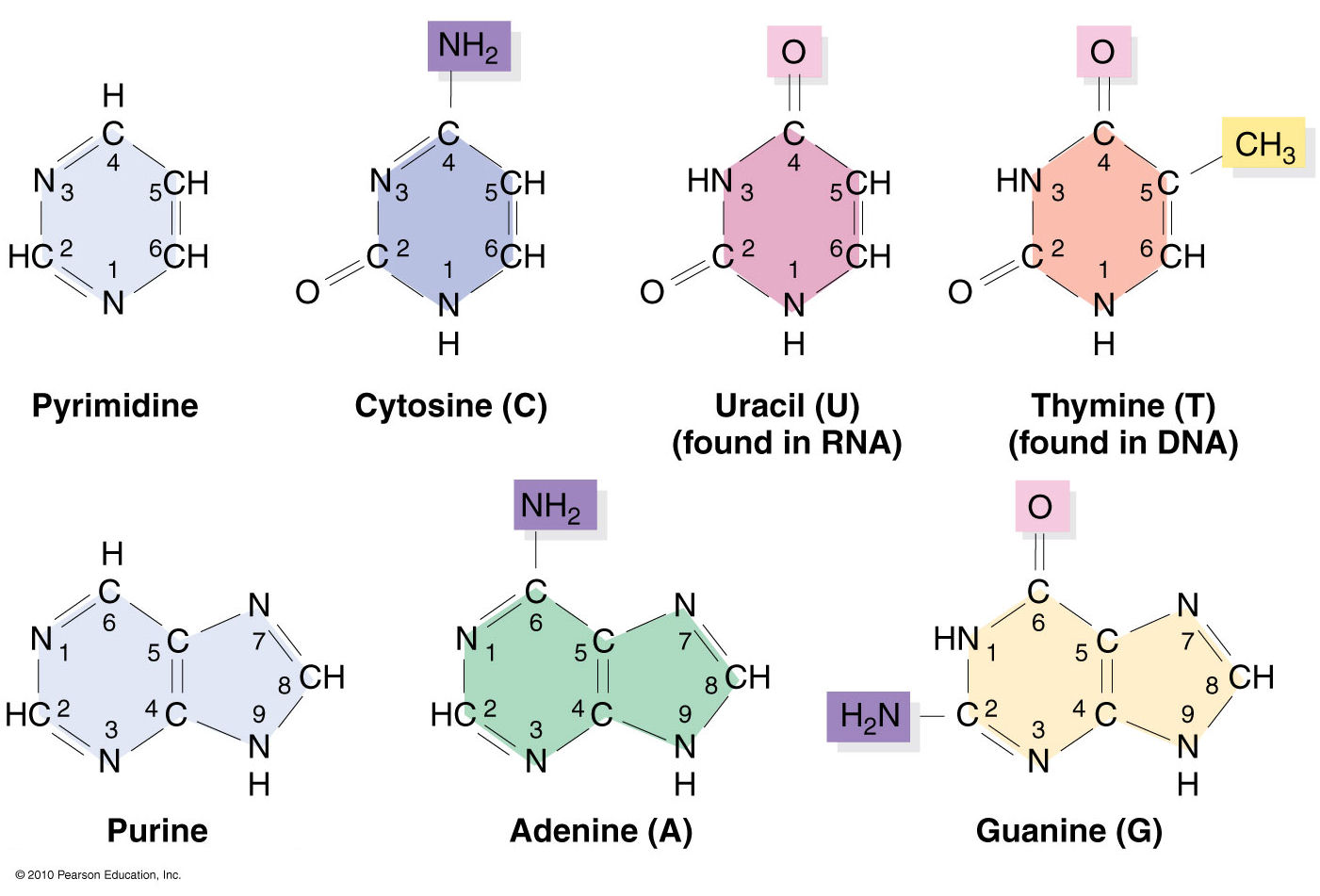

Nucleic acids structural bioinformatics starts with the identification of nucleotides (nts) from atomic coordinates. As biopolymers, RNA and DNA have standard IUPAC names of atoms for the five bases (see the Figure below), sugars (ending with prime, e.g., C1’, O2’), and the phosphate (P, OP1, and OP2). The atomic coordinates (in PDB or mmCIF format) from the Protein Data Bank (PDB) follow the convention.

Trained as a chemist, I am aware that the bases are aromatic, heterocyclic compounds (purines and pyrimidines). Moreover, the five standard bases (A, C, G, T, and U) also share a six-membered ring, with atoms named consecutively (N1, C2, N3, C4, C5, C6). This special feature can be employed to identify nts automatically, from PDB atomic coordinates. The ring skeleton is not influenced by protonation states, tautomeric forms, or modifications in base, sugar or phosphate. Early versions of 3DNA (up to v2.0) used only N1, C2, and C6 atoms to identify an nt: an additional N9 as purine, otherwise as pyrimidine. In 3DNA v2.3 and DSSR, the procedure has been refined to take advantage of all available rings atoms. It is thus more robust against distortions and still works even when any of the N1, C2, C6, or N9 atoms are mutated or missing. This blog post provides further technical details on how the method works.

The template used to identify nts is a purine, with nine base ring atoms. Purine is chosen since it contains atoms of the six-membered ring and N7, C8, and N9. Its atomic coordinates in PDB format are shown below. The coordinates are taken from ‘G’ in the standard reference frame ($X3DNA/config/Atomic_G.pdb). Using ‘A’ as reference won’t make any difference since the RMSD between them is only 0.038 Å.

ATOM 1 N9 G A 1 -1.289 4.551 0.000 1.00 0.00 N

ATOM 2 C8 G A 1 0.023 4.962 0.000 1.00 0.00 C

ATOM 3 N7 G A 1 0.870 3.969 0.000 1.00 0.00 N

ATOM 4 C5 G A 1 0.071 2.833 0.000 1.00 0.00 C

ATOM 5 C6 G A 1 0.424 1.460 0.000 1.00 0.00 C

ATOM 6 N1 G A 1 -0.700 0.641 0.000 1.00 0.00 N

ATOM 7 C2 G A 1 -1.999 1.087 0.000 1.00 0.00 C

ATOM 8 N3 G A 1 -2.342 2.364 0.001 1.00 0.00 N

ATOM 9 C4 G A 1 -1.265 3.177 0.000 1.00 0.00 C

The nt-identification process begins with a mapping of at least three atoms in the purine, followed by a least-squares fit between corresponding atoms. For the five standard bases and most modified ones, the RMSD is normally less than 0.12 Å, as seen in the Figure below. Even the unsaturated dihydrouridine in tRNA has an RMSD of less than 0.25 Å: for the yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB id: e1ehz), for example, it is 0.205 Å for H2U-16, and 0.226 Å for H2U-17. DSSR uses a cutoff of 0.28 Å, covering essentially all nucleotides in the PDB. As an extreme case, the DA1 residue on chain T of PDB id 4ki4 has only three base atoms: N7, C8, and N9 (i.e., no atoms from the six-membered ring). With an RMSD of only 0.005 Å, DSSR still takes it as an nt, properly assigned as ‘A’.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations sometimes produce heavily distorted bases, which is over the default cutoff. Users may change the cutoff to a larger value to accommodate such unusual cases.

In addition to dihydrouridine, the above Figure also shows pseudouridine (PSU), 1-methyladenosine (1MA), 4-thiouridine (4SU), and the heavily modified YYG in tRNA. They are all easily identified using the same scheme. Since the nt-identification method concentrates on base rings, modifications in sugar or the phosphate group do not pose any problem. For example, in tRNA 1ehz, DSSR also identifies O2’-methylguanosine (OMG) and O2’-methylcytidine (OMC) as modified nts.

Two special cases worth mentioning. The ligand IMD in PDB id 1r8e has a five-membered ring. Its atoms are named similarly to those of an nt, and the fitted RMSD is only 0.29 Å. IMD can be filtered out by its missing of the C6 atom and having an N1—C5 covalent bond. The ligand SPM in PDB id 355d is a linear molecule, and its RMSD (1.86 Å) is clearly far off to be taken as an nt.

Another particular case (of a different kind) is the abasic sites, especially in X-ray crystal structures in the PDB. By definition, abasic sites do not have base atoms available. Thus the described method is not applicable to their characterization as nts. As of v1.7.3-2017dec26, however, DSSR has also incorporated abasic sites into the analysis pipeline, by default. The program checks backbone linkage and residue name for appropriate nt assignment. The abasic sites could constitute part of (internal) loops which would otherwise be broken into segments by DSSR.

Overall, I feel confident to say that 3DNA-DSSR has practically solved the problem of identifying nts from atomic coordinates. The method detailed herein (and outlined in the DSSR paper) is simple and easy to understand/implement. Moreover, it has been extensively tested in real-world applications for well over a decade. I’ve yet to find a single case where it does not work as expected.

Over the past couple of months, I’ve further enhanced the DSSR-derived structural features for Q-quadruplexes (G4). One was the implementation of the single descriptor of intramolecular canonical G4 structures with three connecting loops recently proposed by Dvorkin et al. The descriptor contains the number of guanines in the G4 stem, the type and relative direction of loops linking G-tracts of the stem, and the groove-widths associated with lateral loops. For example, PDB entry 2GKU (see the DSSR-enabled PyMOL schematic image below, Fig. 1A) has the following DSSR output.

List of 1 G4-stem

Note: a G4-stem is defined as a G4-helix with backbone connectivity.

Bulges are also allowed along each of the four strands.

stem#1[#1] layers=3 INTRA-molecular loops=3 descriptor=3(-P-Lw-Ln) note=hybrid-1(3+1) UUDU anti-parallel

1 glyco-bond=ss-s groove=-wn- mm(<>,outward) area=14.24 rise=3.58 twist=16.8 nts=4 GGGG A.DG3,A.DG9,A.DG17,A.DG21

2 glyco-bond=--s- groove=-wn- pm(>>,forward) area=13.12 rise=3.71 twist=25.9 nts=4 GGGG A.DG4,A.DG10,A.DG16,A.DG22

3 glyco-bond=--s- groove=-wn- nts=4 GGGG A.DG5,A.DG11,A.DG15,A.DG23

strand#1 U DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG3,A.DG4,A.DG5

strand#2 U DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG9,A.DG10,A.DG11

strand#3 D DNA glyco-bond=-ss nts=3 GGG A.DG17,A.DG16,A.DG15

strand#4 U DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG21,A.DG22,A.DG23

loop#1 type=propeller strands=[#1,#2] nts=3 TTA A.DT6,A.DT7,A.DA8

loop#2 type=lateral strands=[#2,#3] nts=3 TTA A.DT12,A.DT13,A.DA14

loop#3 type=lateral strands=[#3,#4] nts=3 TTA A.DT18,A.DT19,A.DA20

The descriptor=3(-P-Lw-Ln) means that the G4 structure has three layers of G-tetrads, connected via three loops: the first is the Propeller loop in anti-clockwise (negative) direction, then the Lateral loop passing a wide groove anti-clockwise, and finally another Lateral loop passing a narrow groove, also anti-clockwise. The DSSR symbols follow those of Dvorkin et al. but with capital letters L, P, and D for lateral, propeller, and diagonal loops instead of lower case letters (l, p, d) to avoid using subscript for groove-width info. So the 2GKU descriptor 3(-P-Lw-Ln) from DSSR corresponds to 3(-p-lw-ln) of Dvorkin et al.

The DSSR-enabled, PyMOL-rendered, block image in Fig. 1A makes the three G-tetrad layers (squared green blocks) immediately obvious. Other base identities and stacking interactions also become clear — for example, the A24 (in red) stacks on the top G-tetrad, and T1-A20 pair stacks with the bottom G-tetrad.

Two other PDB entries (2LOD and 2KOW) are illustrated in Fig. 1B and Fig. 1C. They have different topologies than 2GKU (Fig. 1A). DSSR is able to characterize all of them consistently.

Figure 1. DSSR-enabled, PyMOL-rendered, block images of five G-quadruplexes. A in red, C in yellow, G (and G-tetrad) in green, and T in blue.

Another G4-related new feature in DSSR is the detection of V-shaped loops in noncanonical G4 structures where one of the four G-G columns (strands) that link adjacent G-tetrads is broken. Two of recent PDB examples with V-loops are shown in Fig. 1D (5ZEV) and Fig. 1E (6H1K). An excerpt of DSSR output for the PDB entry 6H1K is shown below.

List of 1 G4-helix

Note: a G4-helix is defined by stacking interactions of G4-tetrads, regardless

of backbone connectivity, and may contain more than one G4-stem.

helix#1[1] stems=[#1] layers=3 INTRA-molecular

1 glyco-bond=-sss groove=w--n mm(<>,outward) area=12.76 rise=3.47 twist=18.2 nts=4 GGGG A.DG2,A.DG19,A.DG15,A.DG26

2 glyco-bond=s--- groove=w--n pm(>>,forward) area=12.84 rise=3.07 twist=33.4 nts=4 GGGG A.DG1,A.DG20,A.DG16,A.DG27

3 glyco-bond=s--- groove=w--n nts=4 GGGG A.DG25,A.DG21,A.DG17,A.DG28

strand#1 DNA glyco-bond=-ss nts=3 GGG A.DG2,A.DG1,A.DG25

strand#2 DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG19,A.DG20,A.DG21

strand#3 DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG15,A.DG16,A.DG17

strand#4 DNA glyco-bond=s-- nts=3 GGG A.DG26,A.DG27,A.DG28

****************************************************************************

List of 1 G4-stem

Note: a G4-stem is defined as a G4-helix with backbone connectivity.

Bulges are also allowed along each of the four strands.

stem#1[#1] layers=2 INTRA-molecular loops=3 descriptor=2(D+PX) note=UD3(1+3) UDDD anti-parallel

1 glyco-bond=s--- groove=w--n mm(<>,outward) area=12.76 rise=3.47 twist=18.2 nts=4 GGGG A.DG1,A.DG20,A.DG16,A.DG27

2 glyco-bond=-sss groove=w--n nts=4 GGGG A.DG2,A.DG19,A.DG15,A.DG26

strand#1 U DNA glyco-bond=s- nts=2 GG A.DG1,A.DG2

strand#2 D DNA glyco-bond=-s nts=2 GG A.DG20,A.DG19

strand#3 D DNA glyco-bond=-s nts=2 GG A.DG16,A.DG15

strand#4 D DNA glyco-bond=-s nts=2 GG A.DG27,A.DG26

loop#1 type=diagonal strands=[#1,#3] nts=12 GAGGCGTGGCCT A.DG3,A.DA4,A.DG5,A.DG6,A.DC7,A.DG8,A.DT9,A.DG10,A.DG11,A.DC12,A.DC13,A.DT14

loop#2 type=propeller strands=[#3,#2] nts=2 GC A.DG17,A.DC18

loop#3 type=diag-prop strands=[#2,#4] nts=5 GACTG A.DG21,A.DA22,A.DC23,A.DT24,A.DG25

****************************************************************************

List of 2 non-stem G4 loops (INCLUDING the two terminal nts)

1 type=lateral helix=#1 nts=5 GACTG A.DG21,A.DA22,A.DC23,A.DT24,A.DG25

2 type=V-shaped helix=#1 nts=4 GGGG A.DG25,A.DG26,A.DG27,A.DG28

Note that here a new loop type (diag-prop) and topology description symbol (X) are introduced. In developing DSSR in general, and G4-related features in particular, I’ve always tried to follow conventions widely used by the community. Whereas inconsistency exists, I pick up the ones that are in line with other parts of DSSR. For unique DSSR features lacking outside references, I came up my own nomenclature. When DSSR becomes more widely used, it may serve to standardize G4 nomenclatures.

From early on, the --json and --nmr options in DSSR have provided a convenient means to analyze an ensemble of solution NMR structures in the standard PDB/mmCIF format, as those available from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). The usage is very simple, as shown below for the PDB entry 2lod. The parameters for each model can be easily parsed from the output JSON stream.

x3dna-dssr -i=2lod.pdb --nmr --json

A practical example of the DSSR JSON/NMR usage for the analysis of RNA backbone torsion angles can be found on the 3DNA Forum.

While not a practitioner of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, I’ve regularly followed the relevant literature. I know of the popular tools such as MDanalysis, MDTraj, and CPPTRAJ that are dedicated to analyze trajectories of MD simulations. I understand the subtleties MD may have, and I’m also sure of the unique features DSSR has to offer. By design, I made the DSSR interface to MD straightforward, by simply following commonly-used standard data formats: the MODEL/ENDMDL delineated PDB (or the PDBx/mmCIF) format for input, and JSON for output. Overall, I had expected that DSSR would complement the dedicated tools (e.g., MDanalysis, MDTraj, and CPPTRAJ) for MD analysis.

Over the years, DSSR has gradually gained recognition in the MD field. At a meeting, I once heard of a user complaining that DSSR is too slow for the analysis of millions of frames of MD simulations. Yet, without access to a large MD dataset and direct collaborations from a user, the speed issue could not be pursued further. In my experience, I knew DSSR is fast enough for the analysis of NMR ensembles from the PDB. This situation has completely changed recently, after a user reported on the 3DNA Forum on the slowness of DSSR on MD analysis.

Do you have an idea why the backbone parameter for a nucleic acids are so much faster calculated with do_x3dna than with DSSR? Analyzing a trajectory with 100k frames take for a native structure approx. 2 hours with do_x3dna. A native RNA structure with DSSR will take approx. 10 days (10k frames/day). I need to run DSSR, because my system contains an abasic site.

With the above and follow-up information provided, I was able to fix the DSSR algorithm for parsing MD trajectories, among other things. Now DSSR reads a trajectory sequentially frame-by-frame at constant speed. The same 100K frames takes 36 minutes to finish instead of 10 days, which is an increase of 10*24*60/36=400 times. This 100x speedup was later on verified when I tested DSSR on the 1000-structure trajectory the user supplied.

So as of v1.7.8-2018sep01, DSSR is quick enough for real-world applications on MD analysis. In the releases of DSSR afterwards, I’ve further polished the code and added some new features. All things considered, DSSR is bound to become more relevant in the active MD field in the years to come.

By the way, for those who do not like the --nmr option, --md or --ensemble also works. These three alternatives are equivalent to DSSR internally.

As mentioned in the blog post Integrating DSSR into Jmol and PyMOL,

“The small size, zero configuration, extensive features, and robust performance make DSSR ideal to be integrated into other bioinformatics tools.” In addition to the DSSR-Jmol and DSSR-PyMOL integrations which I initiated and got personally involved, other bioinformatics resources are increasingly taking advantage of what DSSR has to offer. Here are a few examples:

Before aligning structures, STAR3D preprocesses PDB files with base-pairing annotation using either MC-Annotate (Gendron et al., 2001; Lemieux and Major, 2002) (for PDB inputs) or DSSR (Lu et al., 2015) (for PDB and mmCIF inputs) and pseudo-knot removal using RemovePseudoknots (Smit et al., 2008).

2014, RNApdbee: In order to facilitate a more comprehensive study, the webserver integrates the functionality of RNAView, MC-Annotate and 3DNA/DSSR, being the most common tools used for automated identification and classification of RNA base pairs.

2018, RNApdbee 2.0: Base pairs can be identified by 3DNA/DSSR (default) (4), RNAView (5), MC-Annotate (3) or newly added FR3D (15).

- The Universe of RNA Structures (URS) web-interface to the URS database (URSDB) makes extensive use of DSSR. For each analyzed structure (including PDB entries), the DSSR text output file (termed “DSSR-file”) is also available. Impressively, the maintainers of URS are quick with DSSR updates. The current version used by the URS website is DSSR v1.7.4-2018jan30.

Forty years after the yeast phenylalanine tRNA structure was solved, modified nucleotides should no longer be an issue for RNA structural analysis, especially for this classic molecule. Automatic processing of modified nucleotides is just one aspect of DSSR’s substantial set of features. Based on my understanding of the field, more structural bioinformatics resources/tools could benefit from DSSR. Simply put, if one’s project is related to 3D DNA or RNA structures, DSSR may be of certain help. It’s just a timing issue that DSSR would benefit a (much) larger community.

DSSR deliberately makes a distinction between ‘stem’ and ‘helix’, as shown below:

a helix is defined by base-stacking interactions, regardless of bp type and backbone connectivity, and may contain more than one stem.

a stem is defined as a helix consisting of only canonical WC/wobble pairs, with a continuous backbone.

By definition, a helix or stem consists of at least two base-pairs with stacking interactions. Helix is more inclusive and may contain more than one stem. This differentiation between ‘helix’ and ‘stem’ naturally leads to the definition of coaxial stacking, another widely used yet vaguely specified concept.

Again, the abstract notion can be best illustrated with a concrete example. In the classic yeast phenylalanine tRNA (PDB id: 1ehz), DSSR identifies that two stems [the acceptor stem (right) and the T stem (left)] are coaxially stacked within one double helix. See the figure below.

In the above schematics cartoon-block representation, each Watson-Crick base pair is rendered as a single, long rectangular block. Base identities of the G–U wobble, and the two non-canonical pairs (left terminal) are illustrated separately, with a larger block size for purines (G and A), and a smaller size for pyrimidines (C, U, and T).

I picked up ‘stem’ as a more specialized duplex because it is widely used in the RNA stem-loop structure, and in describing the four ‘paired regions’ of the classic tRNA cloverleaf secondary structure. On the other hand, ‘helix’ is (to me at least) a more general term, and thus more inclusive. It is worth noting that other terms such as ‘arm’, ‘paired region’, or ‘helix’ etc. have also been used interchangeably in the literature to refer what DSSR designated as ‘stem’.

As a side note, the basic algorithm for identifying helixes/stems in DSSR is also applicable for detecting G-quadruplexes. The same idea of ‘helix’ or ‘stem’ also applies here (see figure below for PDB entry: 5dww). Indeed, as of v1.7.0-2017oct19, DSSR contains a new section for the identification and characterization of G-quadruplexes.

DSSR is “an integrated software tool for dissecting the spatial structure of RNA”. It excels in consolidating the diverse pieces together via a coherent framework, readily accessible in a solid software product. DSSR may well serve as a cornerstone in RNA structural bioinformatics and would facilitate communications in the broad areas related to nucleic acids structures.

Among the rich set of RNA structural features derived by DSSR, the section of “List of stacks” apparently has not drawn much attention from the user community. As noted in the DSSR output,

a stack is an ordered list of nucleotides assembled together via base-stacking interactions, regardless of backbone connectivity. Stacking interactions within a stem are not included.

As always, the concept is best illustrated via concrete examples. Shown below are two such base stacks automatically identified by DSSR in the PDB entry 4p5j, the crystal structure of the tRNA-mimic from Turnip Yellow Mosaic Virus (TYMV) which was analyzed in detail in the 2015 DSSR NAR paper

|

|

| This critical linchpin in the tRNA mimic is stabilized by extensive base-stacking interactions. |

The intricate interactions between the D- and T-loops in the tRNA mimic include a five-base stack. |

The DSSR-introduced schematic block representation makes the base-stacking interactions immediately obvious. One can even easily discern the identity of bases, given the color-coding convention: A-red; C-yellow; G-green; T-blue; U-cyan. For example, the five stacked bases involved in the interaction of the D- and T-loops are: CAAAC

Moreover, longer and more complicate base-stacks can also be auto-detected by DSSR, as shown below for the asymmetric unit of PDB entry 1j8g, the crystal structure of an RNA quadruplex r(UGGGGU)4 at 0.61 Å resolution. Here DSSR identifies two 10-base stacks, each of UGGGGGGGGU (UG8U).

The corresponding DSSR output is as below:

List of 2 stacks

Note: a stack is an ordered list of nucleotides assembled together via

base-stacking interactions, regardless of backbone connectivity.

Stacking interactions within a stem are *not* included.

1 nts=10 UGGGGGGGGU A.U6,A.G5,A.G4,A.G3,A.G2,C.G22,C.G23,C.G24,C.G25,C.U26

2 nts=10 UGGGGGGGGU B.U16,B.G15,B.G14,B.G13,B.G12,D.G32,D.G33,D.G34,D.G35,D.U36