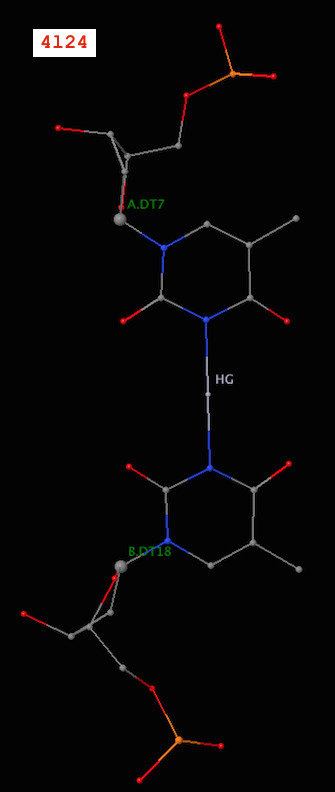

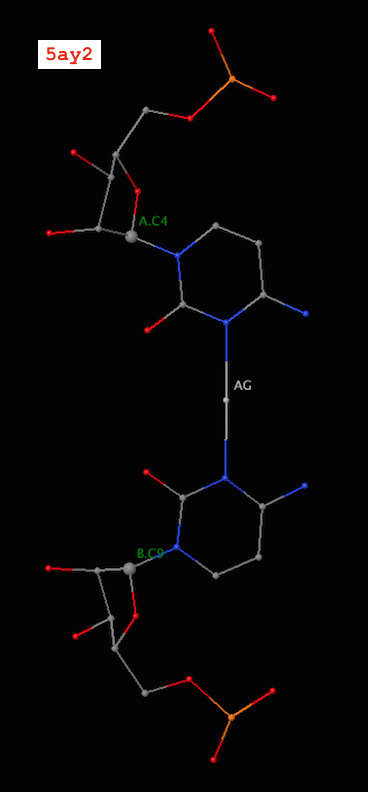

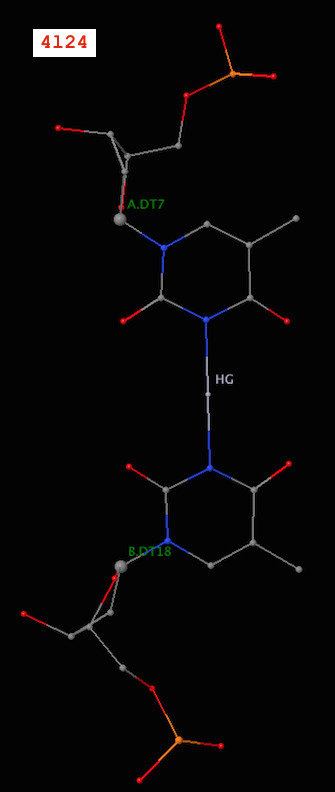

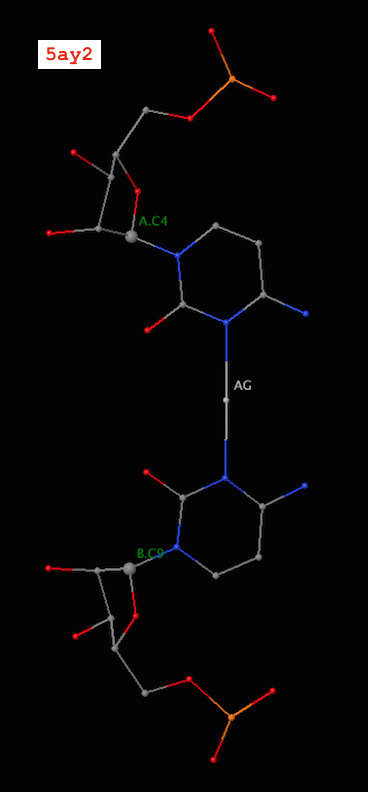

Recently, I became aware of the metallo-base pairs, such as T-Hg-T (PDB id: 4l24) and C-Ag-C (5ay2) from the work of Kondo et al (Pubmed: 24478025 and 26448329). As of v1.4.3-2015oct23, DSSR can detect such metallo-bps automatically, as shown below:

# x3dna-dssr -i=4l24.pdb -o=4l24.out

List of 12 base pairs

nt1 nt2 bp name Saenger LW DSSR

1 A.DC1 B.DG24 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

2 A.DG2 B.DC23 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

3 A.DC3 B.DG22 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

4 A.DG4 B.DC21 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

5 A.DA5 B.DT20 A-T WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

6 A.DT6 B.DT19 T-T Metal n/a cWW cW-W

7 A.DT7 B.DT18 T-T Metal n/a cWW cW-W

8 A.DT8 B.DA17 T-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

9 A.DC9 B.DG16 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

10 A.DG10 B.DC15 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

11 A.DC11 B.DG14 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

12 A.DG12 B.DC13 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

and

# x3dna-dssr -i=5ay2.pdb -o=5ay2.out

List of 24 base pairs

nt1 nt2 bp name Saenger LW DSSR

1 A.G1 B.C12 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

2 A.G2 B.C11 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

3 A.A3 B.U10 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

4 A.C4 B.C9 C-C Metal n/a cWW cW-W

5 A.U5 B.A8 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

6 A.CBR6 B.G7 c-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

7 A.G7 B.CBR6 G-c WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

8 A.A8 B.U5 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

9 A.C9 B.C4 C-C Metal n/a cWW cW-W

10 A.U10 B.A3 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

11 A.C11 B.G2 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

12 A.C12 B.G1 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

13 C.G1 D.C12 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

14 C.G2 D.C11 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

15 C.A3 D.U10 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

16 C.C4 D.C9 C-C Metal n/a cWW cW-W

17 C.U5 D.A8 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

18 C.CBR6 D.G7 c-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

19 C.G7 D.CBR6 G-c WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

20 C.A8 D.U5 A-U WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

21 C.C9 D.C4 C-C Metal n/a cWW cW-W

22 C.U10 D.A3 U-A WC 20-XX cWW cW-W

23 C.C11 D.G2 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

24 C.C12 D.G1 C-G WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

Note the name “Metal” for the metallo-bps. Moreover, the corresponding entries in the ‘dssr-pairs.pdb’ file also include the metal ions, as shown below:

It is worth noting that in a metallo-bp, the metal ion lies approximately in the bp plane. Moreover, it is in the middle of the two bases, which would otherwise not form a pair in the conventional sense.

Curves+ and 3DNA are currently the most widely used programs for analyzing nucleic acid structures (predominantly double helices). As noted in my blog post, Curves+ vs 3DNA, these two programs also complement each other in terms of features. It thus makes sense to run both to get a better understanding of the DNA/RNA structures one is interested in.

Indeed, over the past few years, I have seen quite a few articles citing both 3DNA and Curves+. Listed below are three recent examples:

The helical parameters were measured with 3DNA33 and Curves+.34 The local helical parameters are defined with regard to base steps and without regard to a global axis.

Structure analysis. Helix, base and base pair parameters were calculated with 3DNA or curve+ software packages23,24.

The major global difference between the native and mixed backbone structures is that the RNA backbone is compressed or kinked in strands containing the modified linkage (Fig. 3 B and C, by CURVES) (30). … To compare the three RNA structures at a more detailed and local level, we calculated the base pair helical and step parameters for all three structures using the 3DNA software tools (31) (Fig. 4 and Table S2). [In the Results section]

For each snapshot, the structural parameters—including six base pair parameters, six local base pair step parameters, and pseudorotation angles for each nucleotide—were calculated using 3DNA (31). The two terminal base pairs are omitted for the 3DNA analysis, because they unwind frequently in the triple 2′-5′-linked duplex. [In the Materials and Methods section]

Reading through these papers, however, it is not clear to me if the authors took advantage of the find_pair -curves+ option in 3DNA, as detailed in Building a bridge between Curves+ and 3DNA. Hopefully, this post will help draw more attention to this connection between Curves+ and 3DNA.

JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) is a simple human-readable format that expresses data objects in name-value pairs. Over the years, it has surpassed XML to become the preferred data exchange format between applications. As a result, I’ve recently added the --json command-line option to DSSR to make its numerous derived parameters easily accessible.

The DSSR JSON output is contained in a compact one-line text string that may look cryptic to the uninitiated. Yet, with commonly available JSON parsers or libraries, it is straightforward to make sense of the DSSR JSON output. In this blogpost, I am illustrating how to parse DSSR-derived .json file via two command-line tools, jq and Underscore-CLI.

jq — lightweight and flexible command-line JSON processor

According to its website,

jq is like sed for JSON data – you can use it to slice and filter and map and transform structured data with the same ease that sed, awk, grep and friends let you play with text.

Moreover, like DSSR per se, “jq is written in portable C, and it has zero runtime dependencies.” Prebuilt binaries are available for Linux, OS X and Windows. So it is trivial to get jq up and running. The current stable version is 1.5, released on August 15, 2015.

Using the crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA (1ehz) as an example, here are some sample usages with DSSR-derived JSON output:

# Pretty print JSON

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq .

# Extract the top-level keys, in insertion order

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq keys_unsorted

# Extract parameters for nucleotides

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq .nts

# Extract nucleotide id and its base reference frame

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq '.nts[] | (.nt_id, .frame)'

Underscore-CLI — command-line utility-belt for hacking JSON and Javascript.

Underscore-CLI is built upon Node.js, and can be installed using the npm package manager. It is claimed as ‘the “swiss-army-knife” tool for processing JSON data – can be used as a simple pretty-printer, or as a full-powered Javascript command-line.’

Following the above examples illustrating jq, here are the corresponding commands for Underscore-CLI:

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | underscore print --color

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | underscore keys --color

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | underscore select .nts --color

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | underscore select .nts | underscore select '.nt_id, .frame' --color

jq or Underscore-CLI — which one to use?

As always, it depends. While jq feels more like a standard Unix utility (as sed, awk, grep etc), Underscore-CLI is better integrated into the Javascript language. For simple applications such as parsing DSSR output, either jq or Underscore-CLI is more than sufficient.

I use jq most of the time, but resort to Underscore-CLI for its “smart whitespace”. Here is an example to illustrate the difference between the two:

# z-axis of A.G1 (1ehz) base reference frame

# jq output, split in 5 lines

"z_axis": [

0.799,

0.488,

-0.352

]

# Underscore-CLI, in a more-readable one line

"z_axis": [0.799, 0.488, -0.352]

From early on, the x3dna.org domain and its related sub-domains (e.g., for the forum and the web-interface to DSSR) has been served via shared hosting. By and large, this simple arrangement has worked quite well. Over the years, though, I’ve gradually realized some of its inherent limitations. One is the limited resources available to the 3DNA-related websites. Another is the accessibility issue from countries like China.

To remedy such issues, I’ve recently moved the 3DNA Forum and the web-interface to DSSR to a dedicated web server at Columbia University. Moreover, a duplicate copy of the 3DNA homepage is made available via http://home.x3dna.org hosted at Columbia. The three new websites have been verified to be accessible directly from China.

These updates on x3dna.org not only ensure global accessibility to 3DNA/DSSR, but also allow for more web services to be made available.

As of v1.3.3-2015sep03, DSSR outputs the reference frame of any base or base-pair (bp). With an explicit list of such reference frames, one can better understand how the 3DNA/DSSR bp parameters are calculated. Moreover, third-party bioinformatics tools can take advantage of the frames for further exploration of nucleic acid structures, including visualization.

Let’s use the G1–C72 bp (detailed below) in the yeast phenylalanine tRNA (1ehz) as an example:

1 A.G1 A.C72 G-C WC 19-XIX cWW cW-W

The standard base reference frame for A.G1 is:

{

rsmd: 0.008,

origin: [53.757, 41.868, 52.93],

x_axis: [-0.259, -0.25, -0.933],

y_axis: [-0.543, 0.837, -0.073],

z_axis: [0.799, 0.488, -0.352]

}

And the one for A.C72 is:

{

rsmd: 0.006,

origin: [53.779, 42.132, 52.224],

x_axis: [-0.402, -0.311, -0.861],

y_axis: [0.451, -0.886, 0.109],

z_axis: [-0.797, -0.345, 0.497]

}

The G1–C72 bp reference frame is:

{

rsmd: null,

origin: [53.768, 42, 52.577],

x_axis: [-0.331, -0.283, -0.9],

y_axis: [-0.497, 0.863, -0.089],

z_axis: [0.802, 0.418, -0.427]

}

The beauty of the DSSR JSON output is that the above information can be extracted on the fly. For example, the following commands extract the above frames:

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq '.ntParams[] | select(.nt_id=="A.G1") | .frame'

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json | jq '.ntParams[] | select(.nt_id=="A.C72") | .frame'

x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --json --more | jq .pairs[0].frame

Note that in JSON, the array is 0-indexed, so the first bp (G1–C72) has an index of 0. In addition to jq, I also used underscore to pretty-print the frames.

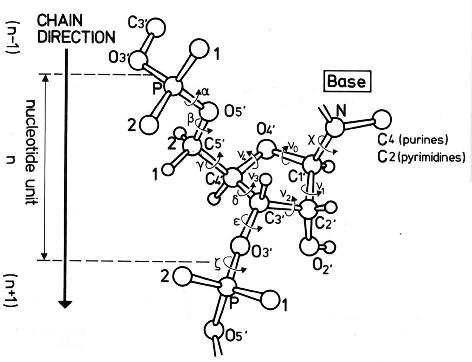

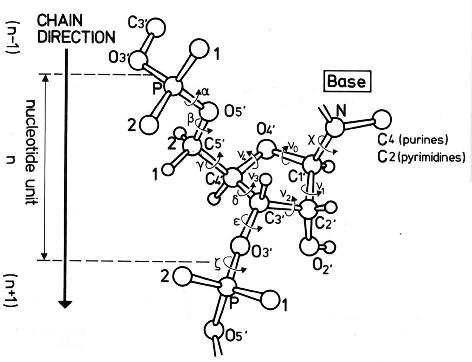

The conformation of the five-membered sugar ring in DNA/RNA structures can be characterized using the five corresponding endocyclic torsion angles (shown below).

v0: C4'-O4'-C1'-C2'

v1: O4'-C1'-C2'-C3'

v2: C1'-C2'-C3'-C4'

v3: C2'-C3'-C4'-O4'

v4: C3'-C4'-O4'-C1'

On account of the five-member ring constraint, the conformation can be characterized approximately by 5 - 3 = 2 parameters. Using the concept of pseudorotation of the sugar ring, the two parameters are the amplitude (τm) and phase angle (P, in the range of 0° to 360°).

One set of widely used formula to convert the five torsion angles to the pseudorotation parameters is due to Altona & Sundaralingam (1972): “Conformational Analysis of the Sugar Ring in Nucleosides and Nucleotides. A New Description Using the Concept of Pseudorotation” [J. Am. Chem. Soc., 94(23), pp 8205–8212]. As always, the concept is best illustrated with an example. Here I use the sugar ring of G4 (chain A) of the Dickerson-Drew dodecamer (1bna), with Matlab/Octave code:

# xyz coordinates of the sugar ring: G4 (chain A), 1bna

ATOM 63 C4' DG A 4 21.393 16.960 18.505 1.00 53.00

ATOM 64 O4' DG A 4 20.353 17.952 18.496 1.00 38.79

ATOM 65 C3' DG A 4 21.264 16.229 17.176 1.00 56.72

ATOM 67 C2' DG A 4 20.793 17.368 16.288 1.00 40.81

ATOM 68 C1' DG A 4 19.716 17.901 17.218 1.00 30.52

# endocyclic torsion angles:

v0 = -26.7; v1 = 46.3; v2 = -47.1; v3 = 33.4; v4 = -4.4

Pconst = sin(pi/5) + sin(pi/2.5) # 1.5388

P0 = atan2(v4 + v1 - v3 - v0, 2.0 * v2 * Pconst); # 2.9034

tm = v2 / cos(P0); # amplitude: 48.469

P = 180/pi * P0; # phase angle: 166.35 [P + 360 if P0 < 0]

The Altona & Sundaralingam (1972) pseudorotation parameters are what have been adopted in 3DNA, following the NewHelix program of Dr. Dickerson. The Curves+ program, on the other hand, uses another (newer) set of formula due to Westhof & Sundaralingam (1983): “A Method for the Analysis of Puckering Disorder in Five-Membered Rings: The Relative Mobilities of Furanose and Proline Rings and Their Effects on Polynucleotide and Polypeptide Backbone Flexibility” [J. Am. Chem. Soc., 105(4), pp 970–976]. The two sets of formula, by Altona & Sundaralingam (1972) and Westhof & Sundaralingam (1983), give slightly different numerical values for the two pseudorotation parameters (τm and P).

Since 3DNA and Curves+ are currently two of the most widely used programs for conformational analysis of nucleic acid structures, the subtle differences in pseudorotation parameters may cause confusions for users who use (or are familiar with) both programs. Over the past few years, I have indeed received such questions via email.

With the same G4 (chain A, 1bna) sugar ring, here is the Matlab/Octave script showing how Curve+ calculates the pseudorotation parameters:

# xyz coordinates of sugar ring G4 (chain A, 1bna)

# endocyclic torsion angles, same as above

v0 = -26.7; v1 = 46.3; v2 = -47.1; v3 = 33.4; v4 = -4.4

v = [v2, v3, v4, v0, v1]; # reorder them into vector v[]

A = 0; B = 0;

for i = 1:5

t = 0.8 * pi * (i - 1);

A += v(i) * cos(t);

B += v(i) * sin(t);

end

A *= 0.4; # -48.476

B *= -0.4; # 11.516

tm = sqrt(A * A + B * B); # 49.825

c = A/tm; s = B/tm;

P = atan2(s, c) * 180 / pi; # 166.64

For this specific example, i.e., the sugar ring of G4 (chain A, 1bna), the pseudorotation parameters as calculated by 3DNA per Altona & Sundaralingam (1972) and Curves+ per Westhof & Sundaralingam (1983) are as follows:

amplitude phase angle

3DNA 48.469 166.35

Curves+ 49.825 166.64

Needless to say, the differences are subtle, and few people will notice/bother at all. For those who do care about such little details, however, hopefully this post will help you understand where the differences actually come from.

For consistency with the 3DNA output, DSSR (by default) also follows the Altona & Sundaralingam (1972) definitions of sugar pseudorotation. Nevertheless, DSSR also contains an undocumented option, --sugar-pucker=westhof83, to output τm and P according to the Westhof & Sundaralingam (1983) definitions.

Each sugar is assigned into one of the following ten puckering modes, by dividing the phase angle (P, in the range of 0° to 360°) into 36° ranges reach.

C3'-endo, C4'-exo, O4'-endo, C1'-exo, C2'-endo,

C3'-exo, C4'-endo, O4'-exo, C1'-endo, C2'-exo

For sugars in nucleic acid structures, C3’-endo [0°, 36°) and C2’-endo [144°, 180°) are predominant. The former corresponds to sugars in ‘canonical’ RNA or A-form DNA, and the latter in sugars of standard B-form DNA. In reality, RNA structures as deposited in the PDB could also contain C2′-endo sugars. One significant example is the GpU dinucleotide platforms, where the 5′-ribose sugar (G) is in the C2′-endo form and the 3′-sugar (U) in the C3′-endo form — see my blog post, titled ‘Is the O2′(G)…O2P H-bond in GpU platforms real?’.

Notes:

- This post is based on my 2011-06-11 blog post with the same title.

- While visiting Lyon in July 2014, I had the opportunity to hear Dr. Lavery’s opinion on adopting the Westhof & Sundaralingam (1983) sugar-pucker definitions in Curves+. I learned that the new formula are more robust in rare, extreme cases of sugar conformation than the 1972 variants. After all, Dr. Sundaralingam is a co-author on both papers. It is possible that in future releases of DSSR, the new 1983 formula for sugar pucker would become the default.

In the DSSR v1.2.7-2015jun09 release, I documented two additional command-line options (--prefix and --cleanup) that are related to the various auxiliary files. As a matter of fact, these two options (among quite a few others) have been there for a long time, but without being explicitly described. The point is not to hide but to simplify — one of the design goals of DSSR is simplicity. DSSR has already possessed numerous key functionality to be appreciated. Before DSSR is firmly established in the RNA bioinformatics field, I beleive too many nonessential “features” could be distracting. While writing and refining the DSSR code, I do feel that some ‘auxiliary’ features could be handy for experienced users (including myself). So along the way, I’ve added many ‘hidden’ options that are either experimental or potentially useful.

On one side, I sense it is acceptable for a scientific software to actually does more than it claims. On the other hand, I have always been quick in addressing users’ requests — as one example, check for the --select option recently introduced into DSSR in response to a user request, and the ‘hidden’ --dbn-break option for specifying the symbol to separate multiple chains or chain breaks in DSSR-derived dot-bracket notation.

Back to --prefix and --cleanup, the purposes of these two closely related options can be best illustrated using the yeast phenylalanine tRNA structure (1ehz) as an example. By default, running x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb will produce a total of 11 auxiliary files, with names prefixed with dssr-, as shown below:

List of 11 additional files

1 dssr-stems.pdb -- an ensemble of stems

2 dssr-helices.pdb -- an ensemble of helices (coaxial stacking)

3 dssr-pairs.pdb -- an ensemble of base pairs

4 dssr-multiplets.pdb -- an ensemble of multiplets

5 dssr-hairpins.pdb -- an ensemble of hairpin loops

6 dssr-junctions.pdb -- an ensemble of junctions (multi-branch)

7 dssr-2ndstrs.bpseq -- secondary structure in bpseq format

8 dssr-2ndstrs.ct -- secondary structure in connect table format

9 dssr-2ndstrs.dbn -- secondary structure in dot-bracket notation

10 dssr-torsions.txt -- backbone torsion angles and suite names

11 dssr-stacks.pdb -- an ensemble of stacks

With ‘fixed’ generic names by default, users can run DSSR in a directory repeatedly without creating too many files. This practice follows that used in the 3DNA suite of programs. However, my experience in supporting 3DNA over the years has shown that users (myself included) may want to explore further some of the files, e.g. ‘dssr-multiplets.pdb’ for displaying the base multiplets (four triplets here). One could easily use command-line (script) to change a generic name to a more appropriate one: e.g., mv dssr-multiplets.pdb 1ehz-multiplets.pdb for 1ehz. A better solution, however, is by introducing a customized prefix to the additional files, and that’s exactly where the --prefix option comes in. The option is specified like this: --prefix=text where text can be any string as appropriate. So running x3dna-dssr -i=1ehz.pdb --prefix=1ehz, for example, will lead to the following output:

List of 11 additional files

1 1ehz-stems.pdb -- an ensemble of stems

2 1ehz-helices.pdb -- an ensemble of helices (coaxial stacking)

3 1ehz-pairs.pdb -- an ensemble of base pairs

4 1ehz-multiplets.pdb -- an ensemble of multiplets

5 1ehz-hairpins.pdb -- an ensemble of hairpin loops

6 1ehz-junctions.pdb -- an ensemble of junctions (multi-branch)

7 1ehz-2ndstrs.bpseq -- secondary structure in bpseq format

8 1ehz-2ndstrs.ct -- secondary structure in connect table format

9 1ehz-2ndstrs.dbn -- secondary structure in dot-bracket notation

10 1ehz-torsions.txt -- backbone torsion angles and suite names

11 1ehz-stacks.pdb -- an ensemble of stacks

The --cleanup option, as its name implies, is to tidy up a directory by removing the auxiliary files generated by DSSR. The usage is very simple:

x3dna-dssr --cleanup

x3dna-dssr --cleanup --prefix=1ehz

The former gets rid of the default ‘fixed’ generic auxiliary files (dssr-pairs.pdb etc), whilst the latter deletes prefixed supporting files (1ehz-pairs.pdb etc).

Recently, I came across and have been surprised by the different assignment of HETATM vs. ATOM records for modified nucleotides in PDB vs. PDBx/mmCIF format. As always, the issue is best illustrated with a concrete example. Here is what I observed in the PDB entry 1ehz, the crystal structure of yeast phenylalanine tRNA at 1.93 Å resolution.

DSSR identifies 14 modified nucleotides (of 11 types) in 1ehz as shown below:

List of 11 types of 14 modified nucleotides

nt count list

1 1MA-a 1 A.1MA58

2 2MG-g 1 A.2MG10

3 5MC-c 2 A.5MC40,A.5MC49

4 5MU-t 1 A.5MU54

5 7MG-g 1 A.7MG46

6 H2U-u 2 A.H2U16,A.H2U17

7 M2G-g 1 A.M2G26

8 OMC-c 1 A.OMC32

9 OMG-g 1 A.OMG34

10 PSU-P 2 A.PSU39,A.PSU55

11 YYG-g 1 A.YYG37

In file 1ehz.pdb downloaded from RCSB PDB, all the 14 modified nucleotides are assigned as HETATM whereas in 1ehz.cif the corresponding records are ATOM. Here is the excerpt for 1MA58 in PDB format:

HETATM 1252 P 1MA A 58 73.770 67.765 34.057 1.00 30.65 P

HETATM 1253 OP1 1MA A 58 72.638 67.886 33.105 1.00 32.84 O

HETATM 1254 OP2 1MA A 58 73.621 68.229 35.450 1.00 29.49 O

HETATM 1255 O5' 1MA A 58 74.315 66.273 34.254 1.00 28.81 O

HETATM 1256 C5' 1MA A 58 74.592 65.439 33.080 1.00 29.42 C

HETATM 1257 C4' 1MA A 58 74.279 63.972 33.383 1.00 33.42 C

HETATM 1258 O4' 1MA A 58 74.880 63.685 34.667 1.00 32.36 O

HETATM 1259 C3' 1MA A 58 72.789 63.573 33.509 1.00 35.13 C

HETATM 1260 O3' 1MA A 58 72.625 62.168 33.250 1.00 36.80 O

HETATM 1261 C2' 1MA A 58 72.560 63.667 35.012 1.00 34.80 C

HETATM 1262 O2' 1MA A 58 71.525 62.828 35.506 1.00 36.27 O

HETATM 1263 C1' 1MA A 58 73.908 63.150 35.551 1.00 33.62 C

HETATM 1264 N9 1MA A 58 74.284 63.494 36.930 1.00 30.36 N

HETATM 1265 C8 1MA A 58 73.887 64.574 37.688 1.00 34.55 C

HETATM 1266 N7 1MA A 58 74.415 64.610 38.899 1.00 33.32 N

HETATM 1267 C5 1MA A 58 75.204 63.469 38.953 1.00 33.37 C

HETATM 1268 C6 1MA A 58 76.031 62.941 39.948 1.00 33.58 C

HETATM 1269 N6 1MA A 58 76.184 63.488 41.134 1.00 41.19 N

HETATM 1270 N1 1MA A 58 76.708 61.803 39.669 1.00 34.48 N

HETATM 1271 CM1 1MA A 58 77.649 61.222 40.626 1.00 31.43 C

HETATM 1272 C2 1MA A 58 76.527 61.216 38.479 1.00 28.43 C

HETATM 1273 N3 1MA A 58 75.793 61.624 37.453 1.00 31.67 N

HETATM 1274 C4 1MA A 58 75.142 62.771 37.747 1.00 33.02 C

The corresponding section in PDBx/mmCIF format is:

ATOM 1252 P P . 1MA A 1 58 ? 73.770 67.765 34.057 1.00 30.65 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A P 1

ATOM 1253 O OP1 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 72.638 67.886 33.105 1.00 32.84 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A OP1 1

ATOM 1254 O OP2 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 73.621 68.229 35.450 1.00 29.49 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A OP2 1

ATOM 1255 O "O5'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.315 66.273 34.254 1.00 28.81 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "O5'" 1

ATOM 1256 C "C5'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.592 65.439 33.080 1.00 29.42 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "C5'" 1

ATOM 1257 C "C4'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.279 63.972 33.383 1.00 33.42 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "C4'" 1

ATOM 1258 O "O4'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.880 63.685 34.667 1.00 32.36 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "O4'" 1

ATOM 1259 C "C3'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 72.789 63.573 33.509 1.00 35.13 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "C3'" 1

ATOM 1260 O "O3'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 72.625 62.168 33.250 1.00 36.80 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "O3'" 1

ATOM 1261 C "C2'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 72.560 63.667 35.012 1.00 34.80 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "C2'" 1

ATOM 1262 O "O2'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 71.525 62.828 35.506 1.00 36.27 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "O2'" 1

ATOM 1263 C "C1'" . 1MA A 1 58 ? 73.908 63.150 35.551 1.00 33.62 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A "C1'" 1

ATOM 1264 N N9 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.284 63.494 36.930 1.00 30.36 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A N9 1

ATOM 1265 C C8 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 73.887 64.574 37.688 1.00 34.55 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A C8 1

ATOM 1266 N N7 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 74.415 64.610 38.899 1.00 33.32 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A N7 1

ATOM 1267 C C5 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 75.204 63.469 38.953 1.00 33.37 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A C5 1

ATOM 1268 C C6 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 76.031 62.941 39.948 1.00 33.58 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A C6 1

ATOM 1269 N N6 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 76.184 63.488 41.134 1.00 41.19 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A N6 1

ATOM 1270 N N1 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 76.708 61.803 39.669 1.00 34.48 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A N1 1

ATOM 1271 C CM1 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 77.649 61.222 40.626 1.00 31.43 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A CM1 1

ATOM 1272 C C2 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 76.527 61.216 38.479 1.00 28.43 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A C2 1

ATOM 1273 N N3 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 75.793 61.624 37.453 1.00 31.67 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A N3 1

ATOM 1274 C C4 . 1MA A 1 58 ? 75.142 62.771 37.747 1.00 33.02 ? ? ? ? ? ? 58 1MA A C4 1

While I have not tested exhaustively, it seems true that PDBx/mmCIF has adopted a different definition of what constitutes a HETATM residue. It is worth noting that results from 3DNA and DSSR/SNAP are not effected by the conflicting assignments.

From the very beginning, 3DNA contains two key programs, analyze and rebuild, for the analysis and rebuilding of nucleic acid 3D structures. The two names are short and to the point, but with one caveat. They are common verbs that can be easily picked up by other software packages. When 3DNA and such packages are installed on the same machine, naming clashes happen. If the 3DNA bin/ directory is searched afterwards, the analyze or rebuild command may have nothing to do with nucleic acid structures at all. Naturally, this naming ambiguity can lead to confusions and frustrations.

I’ve been aware of the rebuild program name conflict for a long time. Recently, I was surprised by another analyze program on my Mac OS X Yosemite. As shown from the following output, the analyze program seems to be installed via Mac port, and it is about analyzing words in a dictionary file.

~ [540] which analyze

/opt/local/bin/analyze

~ [541] analyze -h

correct syntax is:

analyze affix_file dictionary_file file_of_words_to_check

use two words per line for morphological generation

The ambiguous names are exactly the reason that I use x3dna-dssr and x3dna-snap for the two new programs I’ve been working over the past few years. As for the analyze and rebuild programs in 3DNA v2.x, I’d rather leave them as is. 3DNA is now in wide use in other structural bioinformatic pipelines to allow for easy name changes without causing compatibility issues. On a positive side, once you know the problem, fixing it is straightforward. This post is to raise the awareness of the 3DNA user community about such naming conflicts.