Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. [Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74(https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkaa426)).

See the 2020 paper titled "DSSR-enabled innovative schematics of 3D nucleic acid structures with PyMOL" in Nucleic Acids Research and the corresponding Supplemental PDF for details. Many thanks to Drs. Wilma Olson and Cathy Lawson for their help in the preparation of the illustrations.

Details on how to reproduce the cover images are available on the 3DNA Forum.

Structure of a group II intron ribonucleoprotein in the pre-ligation state (PDB id: 8T2R; Xu L, Liu T, Chung K, Pyle AM. 2023. Structural insights into intron catalysis and dynamics during splicing. Nature 624: 682–688). The pre-ligation complex of the Agathobacter rectalis group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase with intron and 5′-exon RNAs makes it possible to construct a picture of the splicing active site. The intron is depicted by a green ribbon, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs represented as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; the 5′-exon is shown by white spheres and the protein by a gold ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Complex of terminal uridylyltransferase 7 (TUT7) with pre-miRNA and Lin28A (PDB id: 8OPT; Yi G, Ye M, Carrique L, El-Sagheer A, Brown T, Norbury CJ, Zhang P, Gilbert RJ. 2024. Structural basis for activity switching in polymerases determining the fate of let-7 pre-miRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol 31: 1426–1438). The RNA-binding pluripotency factor LIN28A invades and melts the RNA and affects the mechanism of action of the TUT7 enzyme. The RNA backbone is depicted by a red ribbon, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs represented as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; TUT7 is represented by a gold ribbon and LIN28A by a white ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Cryo-EM structure of the pre-B complex (PDB id: 8QP8; Zhang Z, Kumar V, Dybkov O, Will CL, Zhong J, Ludwig SE, Urlaub H, Kastner B, Stark H, Lührmann R. 2024. Structural insights into the cross-exon to cross-intron spliceosome switch. Nature 630: 1012–1019). The pre-B complex is thought to be critical in the regulation of splicing reactions. Its structure suggests how the cross-exon and cross-intron spliceosome assembly pathways converge. The U4, U5, and U6 snRNA backbones are depicted respectively by blue, green, and red ribbons, with bases and Watson-Crick base pairs shown as color-coded blocks: A/A-U in red, C/C-G in yellow, G/G-C in green, U/U-A in cyan; the proteins are represented by gold ribbons. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Structure of the Hendra henipavirus (HeV) nucleoprotein (N) protein-RNA double-ring assembly (PDB id: 8C4H; Passchier TC, White JB, Maskell DP, Byrne MJ, Ranson NA, Edwards TA, Barr JN. 2024. The cryoEM structure of the Hendra henipavirus nucleoprotein reveals insights into paramyxoviral nucleocapsid architectures. Sci Rep 14: 14099). The HeV N protein adopts a bi-lobed fold, where the N- and C-terminal globular domains are bisected by an RNA binding cleft. Neighboring N proteins assemble laterally and completely encapsidate the viral genomic and antigenomic RNAs. The two RNAs are depicted by green and red ribbons. The U bases of the poly(U) model are shown as cyan blocks. Proteins are represented as semitransparent gold ribbons. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Structure of the helicase and C-terminal domains of Dicer-related helicase-1 (DRH-1) bound to dsRNA (PDB id: 8T5S; Consalvo CD, Aderounmu AM, Donelick HM, Aruscavage PJ, Eckert DM, Shen PS, Bass BL. 2024. Caenorhabditis elegans Dicer acts with the RIG-I-like helicase DRH-1 and RDE-4 to cleave dsRNA. eLife 13: RP93979. Cryo-EM structures of Dicer-1 in complex with DRH-1, RNAi deficient-4 (RDE-4), and dsRNA provide mechanistic insights into how these three proteins cooperate in antiviral defense. The dsRNA backbone is depicted by green and red ribbons. The U-A pairs of the poly(A)·poly(U) model are shown as long rectangular cyan blocks, with minor-groove edges colored white. The ADP ligand is represented by a red block and the protein by a gold ribbon. Cover image provided by X3DNA-DSSR, an NIGMS National Resource for structural bioinformatics of nucleic acids (R24GM153869; skmatics.x3dna.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

Moreover, the following 30 [12(2021) + 12(2022) + 6(2023)] cover images of the RNA Journal were generated by the NAKB (nakb.org).

Cover image provided by the Nucleic Acid Database (NDB)/Nucleic Acid Knowledgebase (NAKB; nakb.org). Image generated using DSSR and PyMOL (Lu XJ. 2020. Nucleic Acids Res 48: e74).

As of June 24, 2013, the number of 3DNA Forum registrations has passed the 1000 mark. On September 16, 2012, I wrote the post The number of 3DNA forum registrations has reached 500. Thus, in slightly over 9 months, the number has doubled, with approximately 2 registrations per day.

I am glad to see the steady increase of the 3DNA user base. Over the time, I have strived to be responsive to user questions, and made every effort to keep the forum spam free. By and large, employing simple 3DNA-related questions has turned out to be an effective anti-spam strategy. Since the launch of the new forum.x3dna.org in March 2012, I’ve received less than five requests (to the best of my memory) asking for help on registrations. As a recently example, a potential user got stuck with the question about what ‘w’ means in w3DNA. Based on user feedback, I have added hints to some questions to make their answers more obvious. Whatever the reasons, each reported issue has been promptly resolved.

With the release of DSSR and the continuous support of an enthusiastic user community, I have every reason to believe that 3DNA will gain more popularity in the years to come.

As of the beta-r14-on-20130626 release, DSSR has the functionality to identify kink-turns and reverse k-turns given an RNA structure in PDB format.

The k-turn motif was first described by Klein et al. (2001) in the paper The kink-turn: a new RNA secondary structure motif, based on analyses of the H. marismortui large ribosomal unit. It turns out to be a widespread structural motif, now with a dedicated k-turn database hosted by the Lilley laboratory.

Geometrically, k-turn is composed of an asymmetric internal loop, with a sharp kink between the two framing helices and characteristic loop features (including at least one sheared G-A pair and A-minor interactions). Overall, k-turn is a complicated motif, and I am not aware of any published method or available software for its auto-detection.

Previous releases of DSSR has built up all the necessary components to detect key features of a k-turn. Over the past few weeks, I have been focusing on connecting the dots to implement an algorithm for its auto-identification. As of beta-r14-on-20130626, DSSR can locate ‘simple’ k-turns or reverse k-turns from an RNA structure in PDB format. I understand the subtleties and variations of k-turns, and will refine the algorithm in future releases of DSSR.

Without putting k-turns under its umbrella, DSSR appears incomplete in its functionality. Hopefully, detection of k-turns will help DSSR gain more attention from the RNA structure community.

A new paper titled Analyzing and Building Nucleic Acid Structures with 3DNA has been published in JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments). Specifically, the article illustrates 3DNA’s unique capability to characterize and modify DNA structures at the level of the constituent base-pair steps, and highlights a new feature in v2.1 to analyze and align an ensemble of related structures determined with NMR or generated by MD simulations.

Here is the abstract:

The 3DNA software package is a popular and versatile bioinformatics tool with capabilities to analyze, construct, and visualize three-dimensional nucleic acid structures. This article presents detailed protocols for a subset of new and popular features available in 3DNA, applicable to both individual structures and ensembles of related structures. Protocol 1 lists the set of instructions needed to download and install the software. This is followed, in Protocol 2, by the analysis of a nucleic acid structure, including the assignment of base pairs and the determination of rigid-body parameters that describe the structure and, in Protocol 3, by a description of the reconstruction of an atomic model of a structure from its rigid-body parameters. The most recent version of 3DNA, version 2.1, has new features for the analysis and manipulation of ensembles of structures, such as those deduced from nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) measurements and molecular dynamic (MD) simulations; these features are presented in Protocols 4 and 5. In addition to the 3DNA stand-alone software package, the w3DNA web server, located at http://w3dna.rutgers.edu, provides a user-friendly interface to selected features of the software. Protocol 6 demonstrates a novel feature of the site for building models of long DNA molecules decorated with bound proteins at user-specified locations.

A new section dedicated to the JoVE paper will be set up on the 3DNA Forum soon. It will contain all the data files and scripts so our published results can be strictly reproduced. The section should also serve as a platform for open discussions of related protocols.

Over the past six months or so, I’ve been focusing mostly on developing DSSR, a new addition to the 3DNA suite of programs. So what is DSSR, specifically? Why did I bother to create it? How would it be relevant to the nucleic acid structure community?

Literally, DSSR stands for Defining the (Secondary) Structures of RNA. Starting from an RNA structure in PDB format, DSSR employs a set of simple criteria to identify all existent base pairs (bp): both canonical Watson–Crick (WC) pairs and non-canonical pairs with at least one H-bond, made up of normal or modified bases, regardless of tautomeric or protonation state. The classification is based on the six standard rigid-body bp parameters (shear, stretch, stagger, propeller, buckle, and opening), which together rigorously quantify the spatial disposition of any two interacting bases. Moreover, the program characterizes each bp by commonly used names (WC, reverse WC, Hoogsteen, reverse Hoogsteen, wobble, sheared, imino, Calcutta, and dinucleotide platform), the Saenger classification scheme of 28 types, and the Leontis-Westhof nomenclature of 12 basic geometric classes. DSSR also checks for non-pairing interactions (H-bonds or base stacking).

DSSR detects triplets and even higher-order base associations by searching horizontally in the plane of the associated bp for further H-bonding interactions. The program determines helical regions by exploring each bp’s neighborhood vertically for base-stacking interactions, regardless of backbone connection (e.g., coaxial stacking of helices or pseudo helices). Moreover, each helix/stem is characterized by a least-squares fitted helical axis to allow for easy quantification of relative helical geometry. DSSR calculates commonly used backbone (including the virtual η/θ) torsion angles, classifies the main chain backbone into BI/BII conformation and the sugar into C2’/C3’-endo like pucker, identifies A-minor interactions (types I and II), ribose zippers, G quartets, hairpin loops, kissing loops, bulges, internal loops and multi-branch loops (junctions). It also detects the existence of pseudo-knots, and outputs RNA secondary structure in the dot-bracket notation.

Experienced 3DNA users may notice that some of the above outlined functionality (e.g., calculation of torsion angles, identification of all pairs, higher order base associations, and helices) have existed for over a decade. Over the years, I have written several posts (see What can 3DNA do for RNA structures?, and links therein) to advocate 3DNA’s applications in RNA structural analysis. Nevertheless, 3DNA has never been widely used in the RNA structure community, for various possible reasons: (1) the misconception that 3DNA is only for DNA (but not RNA); (2) the basic functionality is split into two programs (find_pair and analyze), and needs to be run several times with different options (default find_pair, and with -s, or -p). Thus even though 3DNA is applicable to RNA structures, it is unnecessarily complicated and confusing (especially to new 3DNA users); (3) 3DNA is command-line driven, consisting of many C programs and scripts, with different styles in specifying options. It has the ‘reputation’ of being powerful, but cryptic and hard to use.

I’ve created DSSR from scratch to take consideration of these factors, by employing my extensive experience in supporting 3DNA, an increased knowledge in RNA structures and refined C programming skills. Implemented in ANSI C as a stand-alone command-line program, DSSR is self-contained. Its executables (on MacOS X, Linux and Windows) have zero runtime dependencies. No setup is necessary; simply put the program into a folder of your choice (preferably one on your command PATH), and it should work. DSSR has sensible default settings and an intuitive output, making it directly accessible to a much broader audience than 3DNA per se. Since its initial release on March 3, 2013, I’ve yet to hear any installation or usage problem. So far, all reported bugs have been verified and fixed promptly. The latest beta release has been checked against all nucleic-acid-containing entries in the PDB, without any known issues.

Overall, DSSR consolidates, refines, and significantly extends 3DNA’s functionality for RNA structural analysis. There are more in DSSR than its simple interface suggests. Piecewise, DSSR may appear nothing new, yet combined together, it has unique features not available anywhere else. Its value will be gradually appreciated as DSSR becomes more widely used by the community. Want to know if your structure contains any Hoogsteen pair, sheared G•A pair, or a dinucleotide platform? DSSR can check it for you, easily.

DSSR-beta already possesses all the basic functionality and has been well tested to serve as a handy tool for RNA structural analysis. I stand firmly behind DSSR, and strive to continuously improve the program. Give it a try, and report back on the 3DNA Forum any issues you have. As always, I respond quickly and concretely to all questions posted there. I hope you enjoying using DSSR as much as I enjoy creating and supporting it!

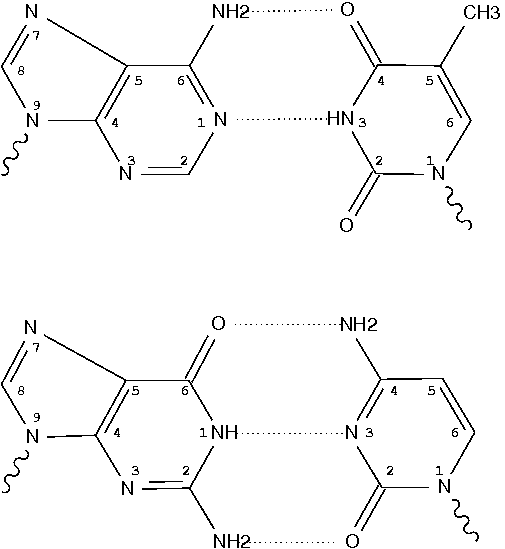

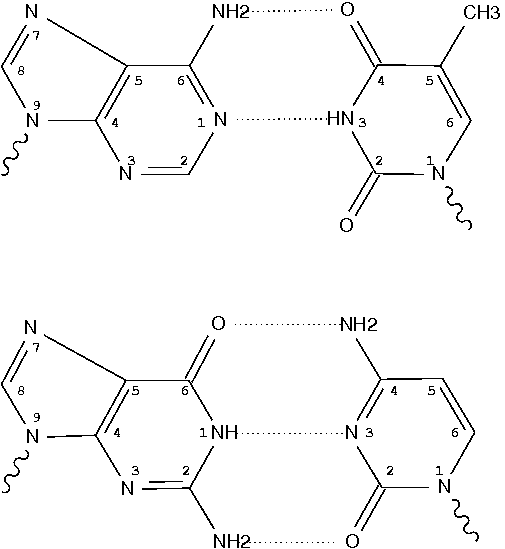

Early on when I started on DNA structures, I read Saenger’s book Principles of Nucleic Acid Structure and became familiar with his classification of the 28 possible base-pairs (bps) for A, G, U(T), and C involving at least two (cyclic) hydrogen bonds (see figure below).

Later on, I read from the 2nd edition of The RNA World book a list of 29 bps compiled by Burkard, Turner & Tinoco. While the one bp discrepancy (28 vs 29) has been in my mind for quite a long while, I had never paid much attention to the issue until recently while adding classifications of RNA bps (among many other functionalities) to 3DNA. A Google search did not help solve the puzzle, so I decided to dig it out by comparing the two lists.

The Burkard et al. list is titled Structures of Base Pairs Involving at Least Two Hydrogen Bonds and it mentions specifically Saenger’s list:

The structures of 29 possible base pairs that involve at least two hydrogen bonds are given in Figures 1–5 (for further descriptions, see Saenger, in Principles of nucleic acid structure, p. 120. Springer-Verlag [1984]).

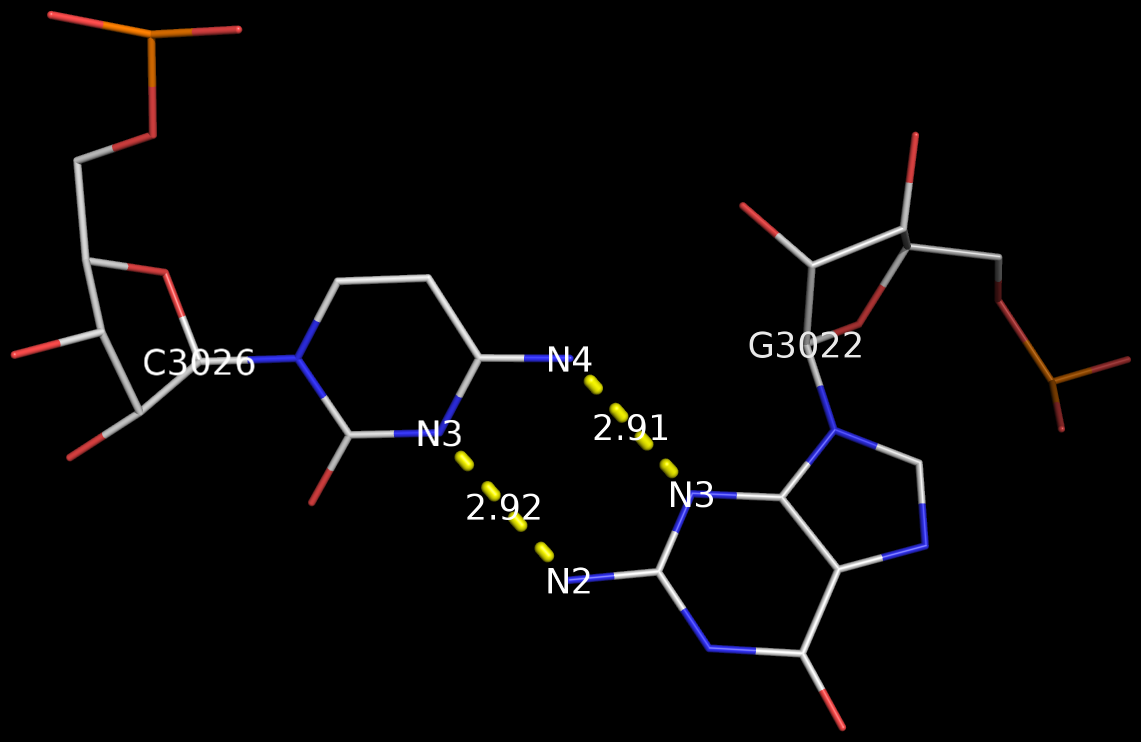

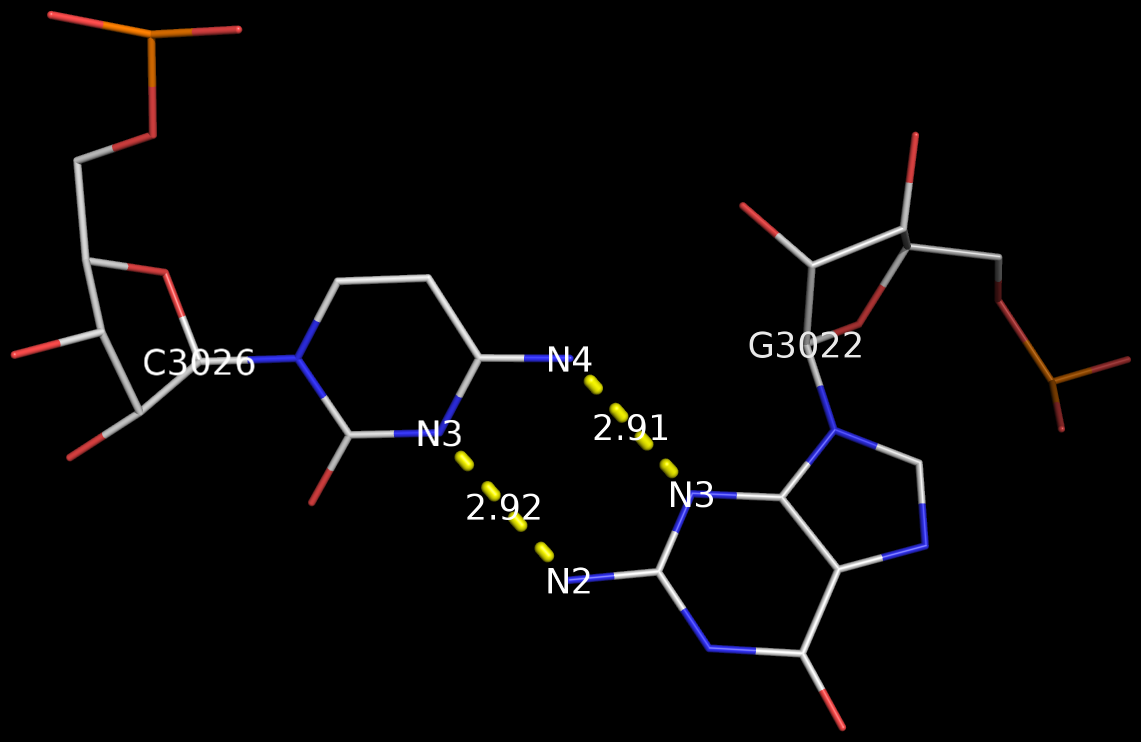

However, in the five figures, Burkard et al. do not provide the corresponding Saenger numbers (I to XXVIII, 1—28) for the 28 common bps; thus it is not immediately obvious which one (i.e., the new addition by Burkard et al.) is missing from Saenger’s list. Under careful scrutiny, the absent bp turns out to be the “G•C N3-amino, amino-N3” pair in Figure 3: “Six possible flipped purine-pyrimidine mismatches.” One example of such G+C pair is found in the 5S ribosomal RNA (chain 9, G3022—C3026) of Haloarcula marismortui in PDB entry 1vq8.

The above figure shows clearly that the G+C bp does indeed have two canonical H-bonds between base atoms, and it is difficult to speculate how it escaped Saenger’s selection criteria. In the upcoming new 3DNA component, I am listing this bp as number XXIX (29), along with the other 28 base pairs.

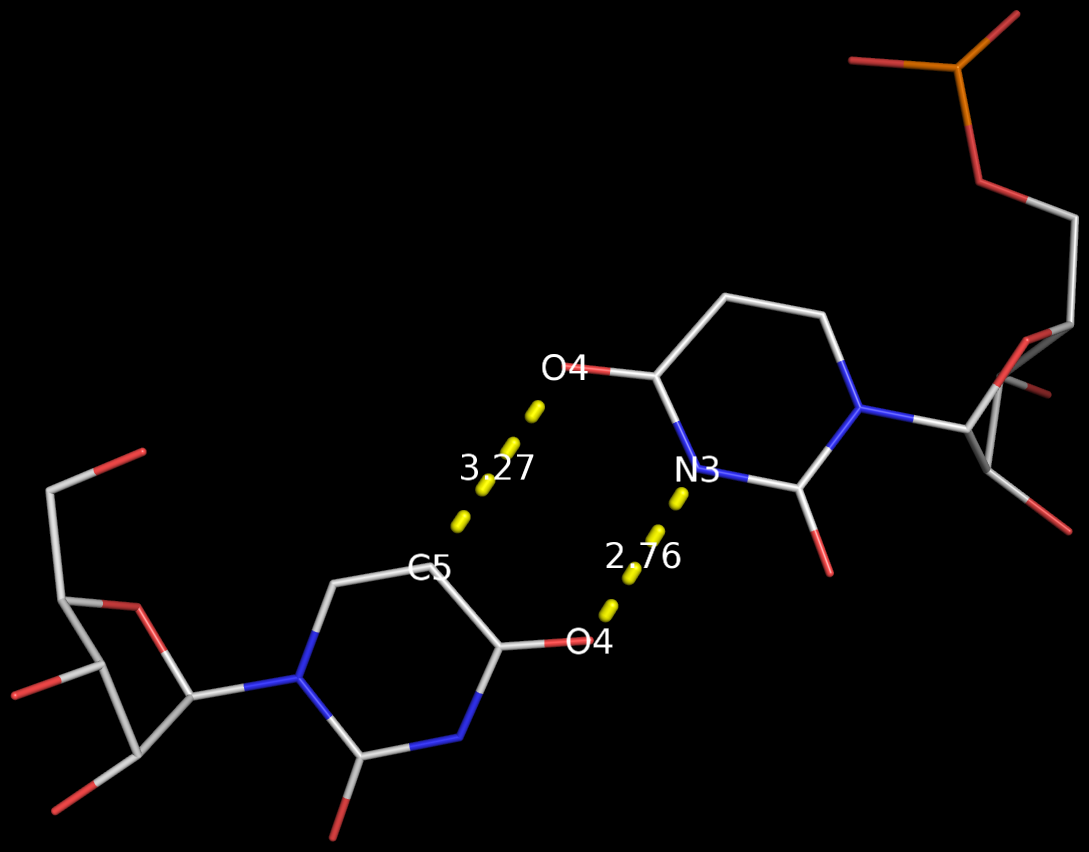

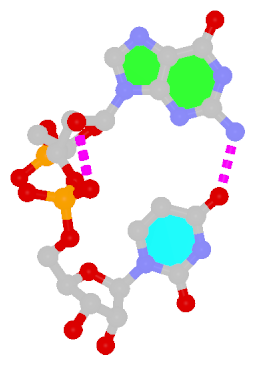

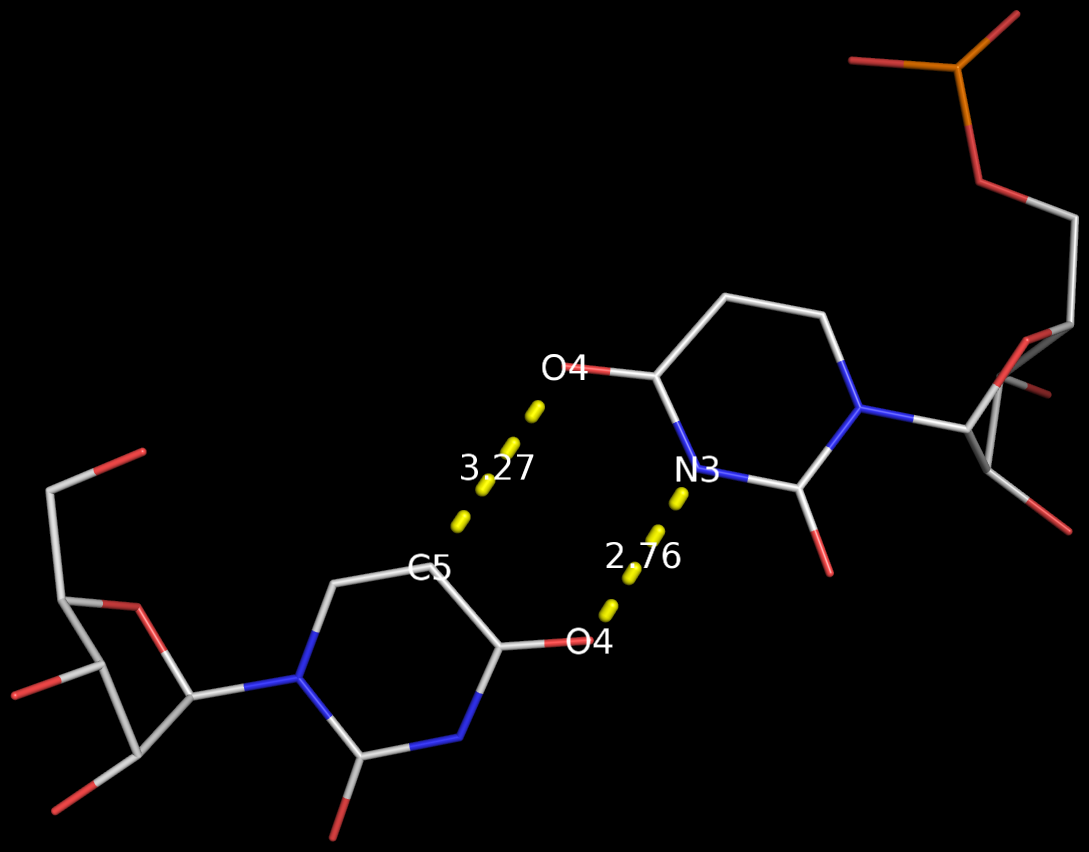

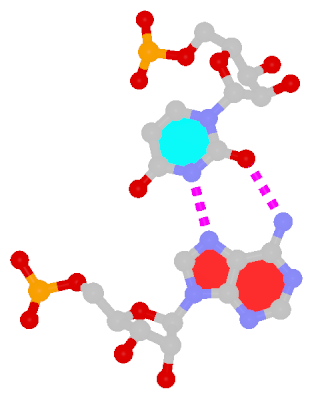

Recently, I came across the so-called Calcutta U-U base pair (bp) [see figure below] while reading articles on C-H…O contacts in nucleic acid structures. Not familiar with this named pair before, I was curious to find out what it’s about. After some searching, I traced the origin of the Calcutta U-U bp to the following two papers published by Sundaralingam’s group during the middle 1990s:

We have called the novel U•U base pair, where the Hoogsteen face of one of the pyrimidines is involved in a C5-H—O4 hydrogen bond, the ‘Calcutta Base Pair’, since it was announced at the International Seminar-cum-School on Macromolecular Crystallographic Data held in Calcutta, November 16-20, 1995.

We recently discovered a novel U•U base pair, referred to as the Calcutta base pair, in the crystal structure of an RNA hexamer UUCGCG (Ref. 18). The two uracil bases form a conventional N(3)-H…O(4) and an unconventional C(5)-H…O(2) hydrogen bond (Fig. 3a). The C-H…O interaction is entirely ‘voluntary’ and not ‘forced’, underlining its importance in base mispairing.

3DNA has no problem to identify the Calcutta U-U bps (or any pair for that matter); an example is shown below based on the RNA hexamer UUCGCG structure (PDB entry: 1osu) solved by Sundaralingam and colleagues.

In the new 3DNA component I’ve been working on (and to be released soon), the Calcutta U-U pair is characterized as below:

1/A.U1 3/A.U2 [U-U] Calcutta 00-n/a tHW -MW

anti C3'-endo 8.9 --- anti C3'-endo 30.3

dcc=11.18 dnn=8.48 dmm=7.58 tor=-174.1

H-bonds[2]: "O4(carbonyl)-N3(imino)[2.76]; C5-O4(carbonyl)[3.27]"

Shear=-3.67 Stretch=-0.52 Stagger=-0.89

Buckle=-1.41 Propeller=-16.03 Opening=-90.67

The Calcutta pair is explicitly named, along with other named base pairs (e.g., Watson-Crick [WC], Wobble, and Hoogsteen bps). It is classified as type tHW (trans with Hoogsteen/WC interacting edges), following the commonly used Leontis-Westhof nomenclature. It does not belong to any of the 28 bps (00-n/a) with at least two conventional H-bonds, as categorized by Saenger. In 3DNA, the Calcutta U-U pair is of M-N type, designated as -MW.

Among the well-known named base pairs, some are after the scientists who discovered them (e.g., WC and Hoogsteen bps), while others are based on chemical/geometrical features (e.g., Wobble and Sheared G-A bps), or a combination of both (e.g., reversed WC/Hoogsteen bps). The Calcutta U-U pair is unique in that it is named after a place in India:

Kolkata, or Calcutta, is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal. … While the city’s name has always been pronounced Kolkata or Kolikata in Bengali, the anglicized form Calcutta was the official name until 2001, when it was changed to Kolkata in order to match Bengali pronunciation.

Prior to v2.1, 3DNA does not provide any direct support for the analysis of molecular dynamics (MD) simulations trajectories of nucleic acid structures. Nevertheless, over the years, I noticed some significant applications of 3DNA in the active MD field; see my blog post (December 6, 2009) titled 3DNA in the PCCP nucleic acid simulations themed issue. In January 2011, I released a set of two Ruby scripts specifically aimed to facilitate the analysis of MD simulations trajectories. Thereafter (as of 3DNA v2.1), I have significantly refined and expanded the Ruby scripts, and consolidated the functionality under one umbrella, x3dna_ensemble with multiple sub-commands (analyze, block_image, extract, and reorient). I believe x3dna_ensemble would make it straightforward to analyze ensembles (NMR or MD simulations trajectories) of nucleic acid structures.

Under this background, I am glad to read recently an article titled Structure, Stiffness and Substates of the Dickerson-Drew Dodecamer in J. Chem. Theory Comput. where 3DNA was used extensively. This work represents a re-visit of the classic Dickerson−Drew B-DNA dodecamer d-[CGCGAATTCGCG]2 using state-of-the-art MD simulations with different ionic conditions and solvation models, and compares the MD trajectories with modern crystallographic and NMR data. Among the author list (Tomas Drsata, Alberto Perez, Modesto Orozco, Alexandre Morozov, Jiri Sponer, and Filip Lankas) are some well-known figures in the MD field of nucleic acid structures.

Reading through the text, I am not sure if the newly available functionality of x3dna_ensemble was used. From the excerpts of the citations given below, however, it seems obvious that 3DNA is now well-accepted by the MD community.

Snapshots taken in 10 ps intervals were analyzed using the 3DNA program.43 From 3DNA outputs, time series of conformational parameters were extracted. These included the intra-base-pair coordinates (buckle, propeller, opening, shear, stretch, and stagger), inter-base-pair or step coordinates (tilt, roll, twist, shift, slide, and rise) as well as groove widths (based on P−P distances), backbone torsions, and sugar puckers.

Contrary to the original work of Lankas et al.,31 the intra-base-pair and step coordinates used here are those defined by 3DNA.43

Here, we apply this model together with the 3DNA definitions of the intra-base-pair and step coordinates.43

However, important differences remain, and non- negligible differences are in fact observed between individual experimental structures also in the central part of DD, even though the intra-base-pair and step coordinates are computed using the same coordinate definitions64 (we consistently use the 3DNA coordinates in this work).

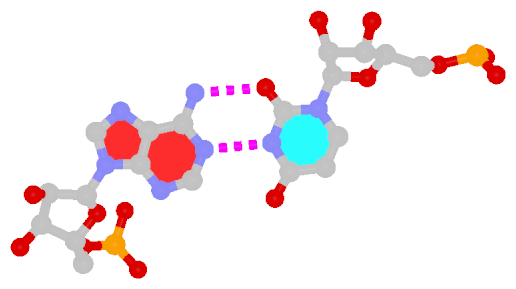

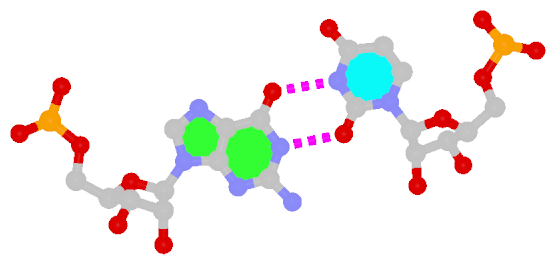

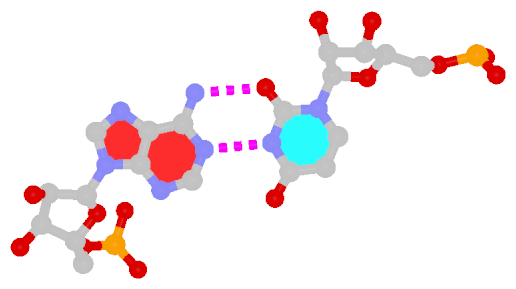

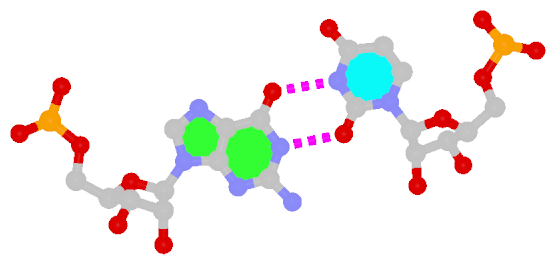

In the field of nucleic acid structures, especially in the ‘RNA world’, we often hear named base pairs (bp). Among those, the Watson-Crick (WC) A–U and G–C bps (see figure below) are by far the most common.

Closely related to the WC bps are the so-called reversed WC (rWC) bps, where the relative glycosidic bond are reversed; instead of being on the same side of the bases as in WC bps shown above, they are now on opposite sides in rWC bps as shown below. According to the Leontis-Westhof (LW) bp classification scheme, the rWC bps belong to trans WC/WC. Following Saenger’s numbering, the rWC A+U bp corresponds to XXI, and the rWC G+C bp XXII.

In the figures below, the name of each type of bp and its LW & Saenger designations (separated by ‘;’) are noted under the corresponding image. All images are generated with 3DNA; for easy comparison, each bp is oriented in the reference frame of the leading base.

|

|

| Reversed WC A+U pair |

Reversed WC G+C pair |

| trans WC/WC; XXI |

trans WC/WC; XXII |

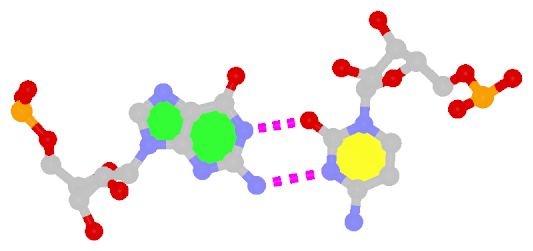

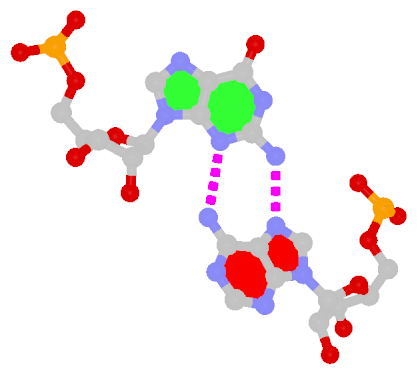

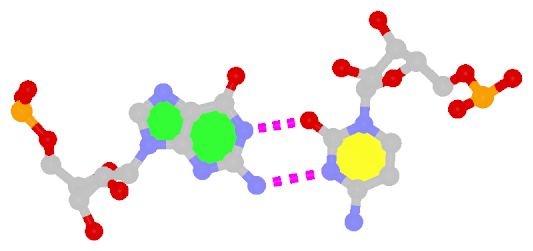

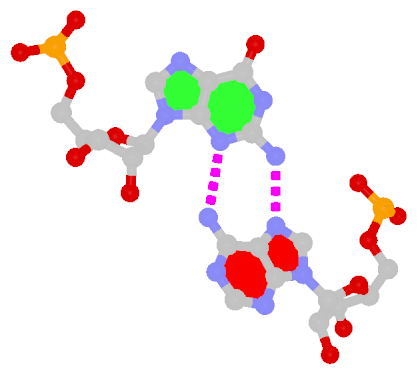

The next most famous one is the Hoogsteen A+U bp, which also has a reverse variant, i.e., the rHoogsteen A–U bp (see figure below). Now the major groove edge of A, termed the Hoogsteen edge by LW, is used for pairing with U.

|

|

| Hoogsteen A+U pair |

Reversed Hoogsteen A–U pair |

| cis Hoogsteen/WC; XXIII |

trans Hoogsteen/WC; XXIV |

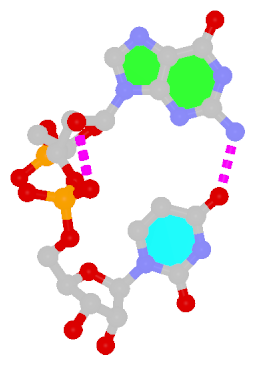

First proposed by Crick in 1966 to account for the degeneracy in codon–anticodon pairing, the Wobble bp is an essential component (in addition to the WC bps) in forming double helical RNA secondary structures.

|

| Wobble G–U pair |

| cis WC/WC; XXVIII |

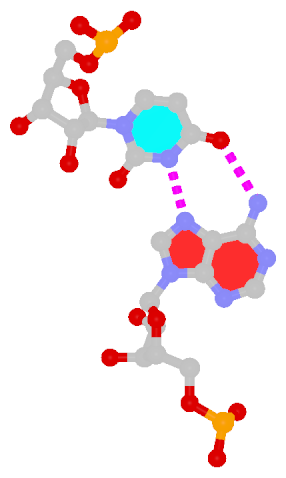

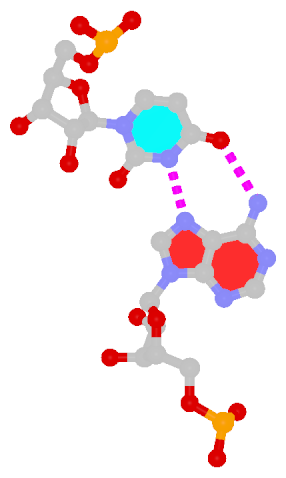

The sheared G–A base pair

Sheared G–A is a commonly found non-WC bp in both DNA and RNA structures. Noticeably, tandem sheared G–A bps introduce distinct stacking geometry. Here G uses its minor groove edge, termed the sugar edge by LW, to pair with the Hoogsteen edge of A.

|

| Sheared G–A pair |

| trans Suger/Hoogsteen; XI |

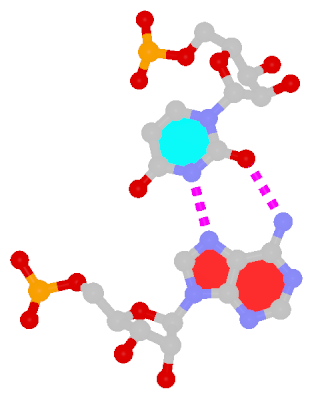

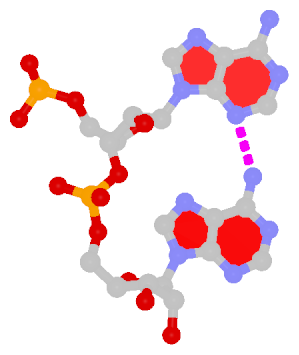

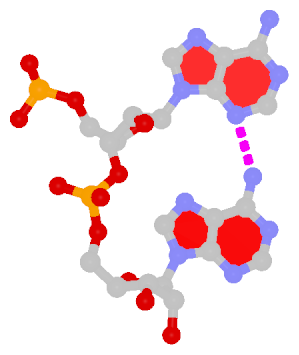

Dinucleotide platforms

Dinucleotide platforms are formed via side-by-side pairing of adjacent bases; the most common of which are GpU and ApA. Here the sugar (minor-groove) edge of the 5′ base interacts with the Hoogsteen (major-groove) edge of the 3′ base. Since there is only one base-base H-bond in dinucleotide platforms, no Saenger classification is available. In 3DNA output, the GpU dinucleotide platform is designated as G+U, and ApA as A+A.

|

|

| GpU dinucleotide platform |

ApA dinucleotide platform |

| cis Sugar/Hoogsteen; n/a |

cis Sugar/Hoogsteen; n/a |

Other named base pairs

There exist other named bps in RNA literature, e.g., G⋅A imino, A⋅C reverse Hoogsteen, G⋅U reverse Wobble etc. In the my experience, they are (much) less commonly used than the ones illustrated above.

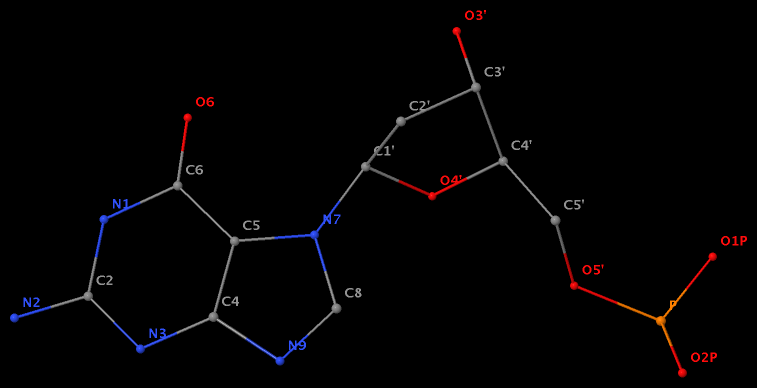

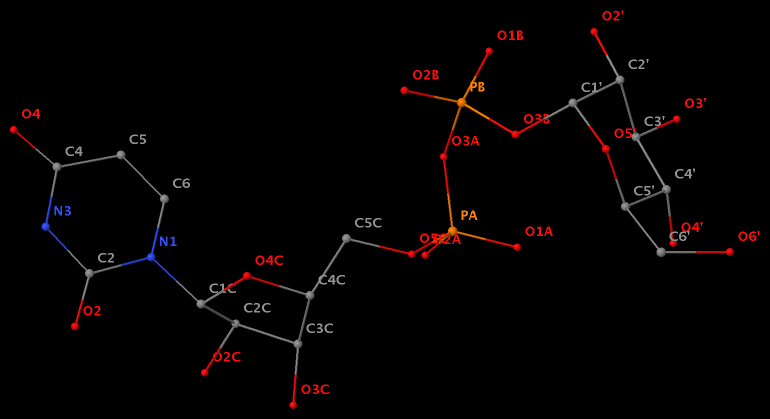

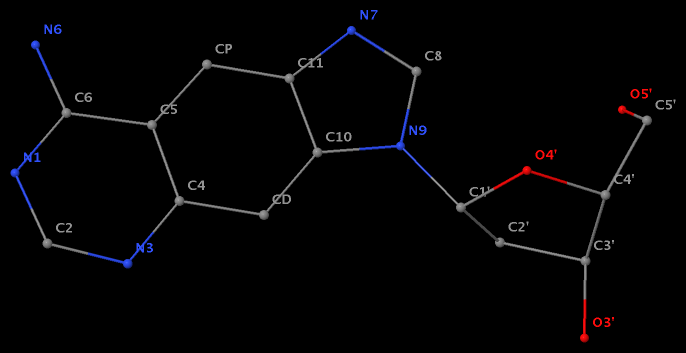

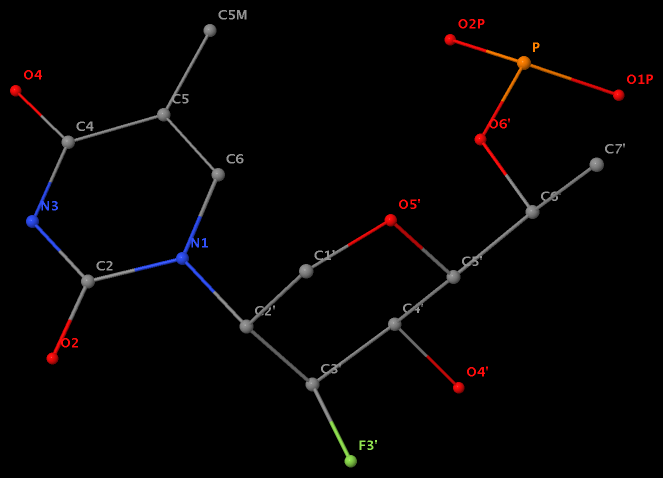

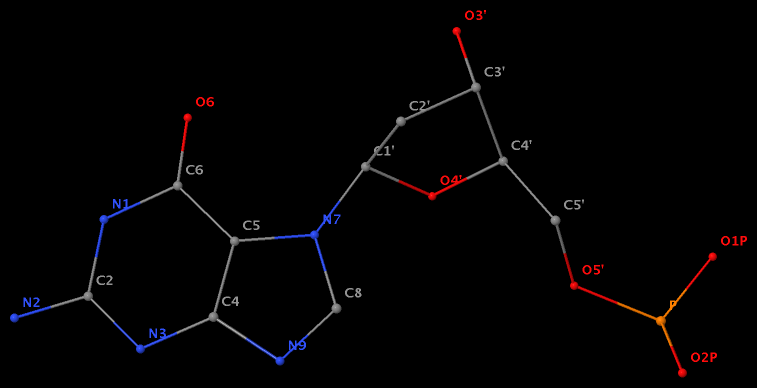

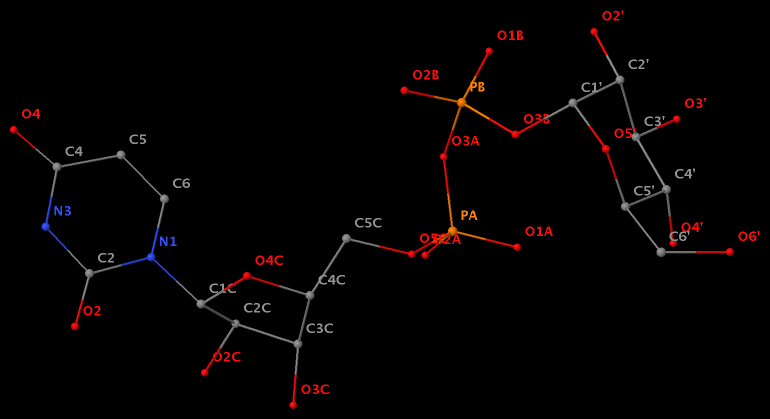

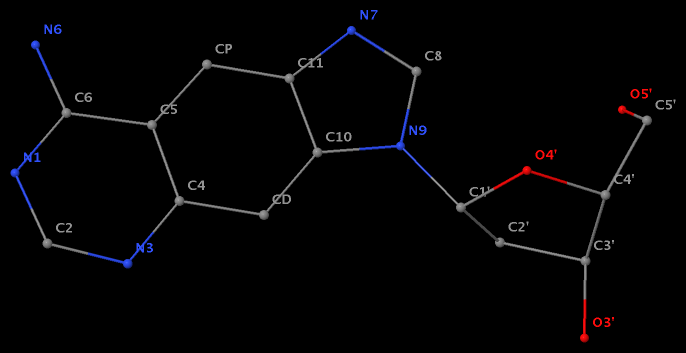

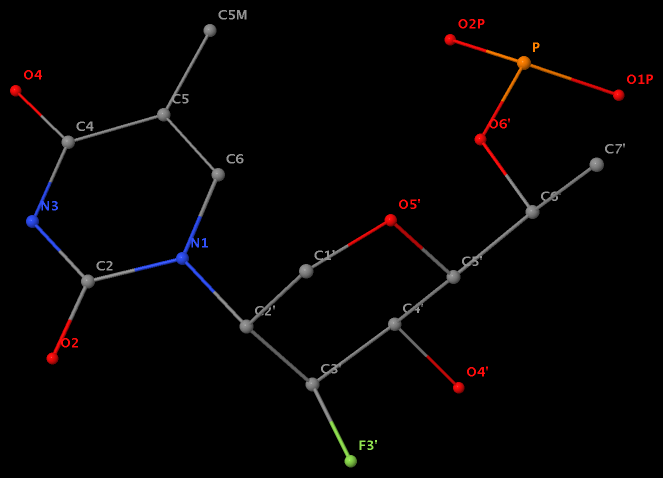

Glycosidic bond “is a type of covalent bond that joins a carbohydrate (sugar) molecule to another group, which may or may not be another carbohydrate.” In nucleic acid structures, the other group is a nucleobase, and the predominated type is the N-glycosidic bond where the purine (A/G) N9 or pyrimidine (C/T/U) N1 atom connects to the C1′ atom of the five-membered (deoxy) ribose sugar ring. Another well-known type is the C-glycosidic bond in pseudouridine, the most common modified base in RNA structures where the C5 atom instead of N1 is linked to the C1′ atom of the sugar ring.

Recently, I performed a survey of all nucleic-acid-containing structures in the PDB/NDB database to see how many types of glycosidic bond are there. As always, I noticed some inconsistencies in the data: nucleotides with disconnected base/sugar, a base labeled as U but with pseudoU-type C-glycosidic bond. Shown below are a few unusual types of glycosidic bond in otherwise seemingly “normal” structures:

- The residue GN7 (number 28 on chain A) in PDB entry 1gn7 contains a N7-glycosylated guanine.

- The residue UPG (number 501 on chain A) in PDB entry 1y6f has sugar C1C (instead of C1′) atom connects to N1 of U.

- The residue XAE (number 11 on chain B) in PDB entry 2icz contains a benzo-homologous adenine.

- The residue F5H (number 206 on chain B) in PDB entry 3v06 has N1 of U connects to C2′ of a six-membered sugar ring.

The unusual glycosidic bond has implications in 3DNA calculated parameters, for example the chi torsion angle. Identifying such cases would help refine 3DNA to provide sensible parameters and to avoid possible misinterpretations.